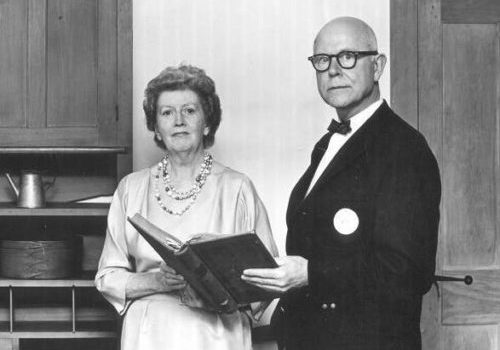

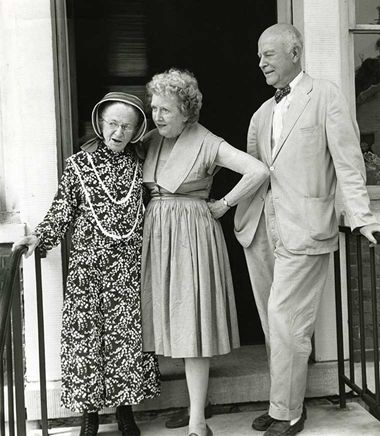

Dr. Edward Deming & Faith Andrews

– Richmond, Massachusetts –

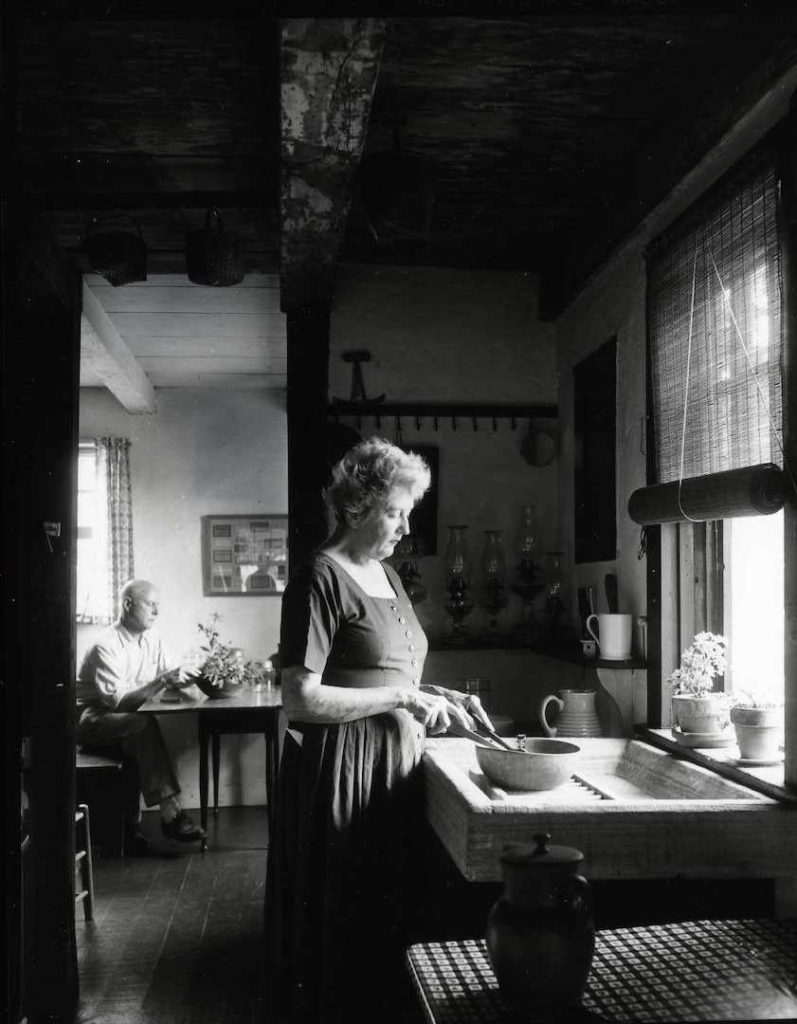

The significance of Dr. Edward Deming (“Ted”) (1894-1964) and Faith Young Andrews (1896-1990) to the history of collecting and studying the material culture of the Shakers cannot be understated. From the 1920s through the 1960s, the Andrewses assembled a vast collection of Shaker material—spanning furniture, domestic objects, tools, garments, visionary artworks, and manuscripts—that, today, can be seen in several important public and private collections. Their work not only preserved a wealth of significant artifacts but, further, helped canonize Shakerism within the history of American religion and culture.

Both Ted and Faith Andrews were born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, about five miles from the Shaker settlement in Hancock. According to their memoir, Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life (1975), in the early 20th century, Shaker design and craftsmanship were unappreciated outside of the Society, particularly within the halls of our nation’s revered academies and museums. “Neither of us knew much more about them than the current gossip that they were a ‘peculiar’ sect,” they wrote. This all changed when, in 1923, the Andrewses drove by the Hancock community and decided to drop by the brick dwellinghouse “cook-room” to purchase two loaves of freshly baked bread. Following that fated visit, they recalled:

“We knew our appetite would not be satisfied with bread alone.”

A charming tale to be sure, but on closer examination, the Andrewses’ interest in the lives and works of the Shakers goes back further than this quaint jaunt in September of 1923. In fact, Ted’s interest was sparked in 1918/1919 while he was stationed at Camp Devens in Shirley, Massachusetts. In a journal entry dated June 22, 1919, he wrote:

“As I was walking to work yesterday morning, I thought how bold and adventurous a scheme it would be to live this fall and winter and next spring with the Shakers of West Pittsfield or Lebanon, studying and amassing notes in their ways and customs, endeavoring to analyze their characters and their religion…”

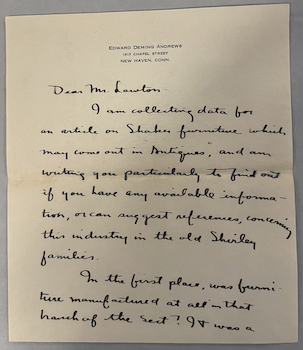

Ted Andrews was a graduate of Pittsfield High School and, later, Amherst College. He worked briefly as a reporter for the Springfield Republican before entering the army on August 25, 1917. In 1918-1919, Ted was stationed at Camp Devens where he began participating in a salon of sorts—a group hosted by Frank Lawton and his daughter Shirley that came together to discuss literature, philosophy, politics, and culture. In her memoir, Shirley Lawton refers to Ted as “the Poet Sargent,” noting that he and his wife went on to become “experts on all matters of the vanishing Shaker sect.” Curiously, it was during this time at Camp Devens—in 1918—that the adjacent Shaker community in Harvard, Massachusetts, was closed and consolidated by the Shaker ministry. Clara Endicott Sears (1863-1960), who had opened her museum at Fruitlands in 1914 and published Gleanings from Shaker Journals in 1916, purchased a Shaker office, moving the structure to Fruitlands to be used as a space to display her Shaker collections and preserve the Shaker legacy.

While numerous scholars have speculated that it was the Andrewses dealings in the American antiques trade that set them on the Shaker path, historian and biographer Mario De Pillis, it was the Lawtons’s salon and the Camp’s proximity to the defunct communities in Harvard and Shirley that prompted Ted’s interest in Shakerism. Indeed, a close examination of diary entries from the Camp Devens period illustrates Ted’s experience at the Lawtons’ to be transformative. Not only did their influence secure his future vocation as a writer/scholar, but further, Ted developed a set of principles that precipitated his desire to preserve the beauty of Shaker life in the wake of rampant materialism, which he believed to be the dominant force over American culture.

At his core, Ted was an idealist. Although he did not move forward with his “bold and adventurous scheme” to live among the Shakers, he did go on to devote himself to elevating Shakerism—its principles and works—into the canons of American history and museum culture.

Shortly after leaving Camp Devens in 1919, Ted met Faith Young at a dance in their hometown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and they married two years later. Faith was a graduate of Berkshire Community College, and her proficiency in typing, shorthand, and editing was indispensable to their later work. From nearly their first meeting, Ted and Faith began collecting antiques—“colonial pieces,” according to Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life. By 1925, they collected exclusively Shaker and, over the next twenty-five years, acquired the majority of their important collection. In 1923, they moved to New Haven, Connecticut, so Ted could pursue a Ph.D. in education and eventually pursue a career as a high school principal. After graduating in 1930, Ted was unable to find full-time employment, so he accepted a part-time position as a temporary curator of history at the State Museum in Albany.

When asked about this formative period, Faith recollected:

“During the Depression, we did the major part of our collecting and a great deal of research… We were in the Victorian house [in Pittsfield] with Dad. It was a very happy situation and every day we went to Hancock, or New Lebanon, or/and Watervliet and then we followed to other New England communities.”

By the 1930s, the Andrewses had established a warm rapport with practicing Shakers and, over time, they were able to sway some crucial Shaker allies to help support their preservation efforts. Sister Sarah “Sadie” Neale (1849-1948) of Mount Lebanon, Sister Alice Smith (1884-1935) of Hancock, and Eldress Prudence A. Stickney (1860-1950) of Sabbathday Lake, were close family friends who facilitated several important acquisitions, such as the Andrewses’ collection of gift drawings that, by some accounts, were saved from the rubbish bin by Sister Alice Smith.

According to De Pillis, the characteristic that distinguishes the Andrews collection from the efforts of his contemporaries, (such as Wallace H. Cathcart of the Western Reserve Historical Society, Edward Brockway Wright of the Wright Shaker Collection at Williams College, Clara Endicott Sears of Fruitlands, and others), is that the Andrewses, “collected not just documents and furniture but also pews, books, stoves, stools, shovels, hymnals, baskets, drawings, textiles, hand tools, pots and pans, giant ledgers, massive shop tools, decaying Shaker seed packages, and every other concrete aspect of Shaker life… They were in it for the entire culture, not just the history of the furniture.”

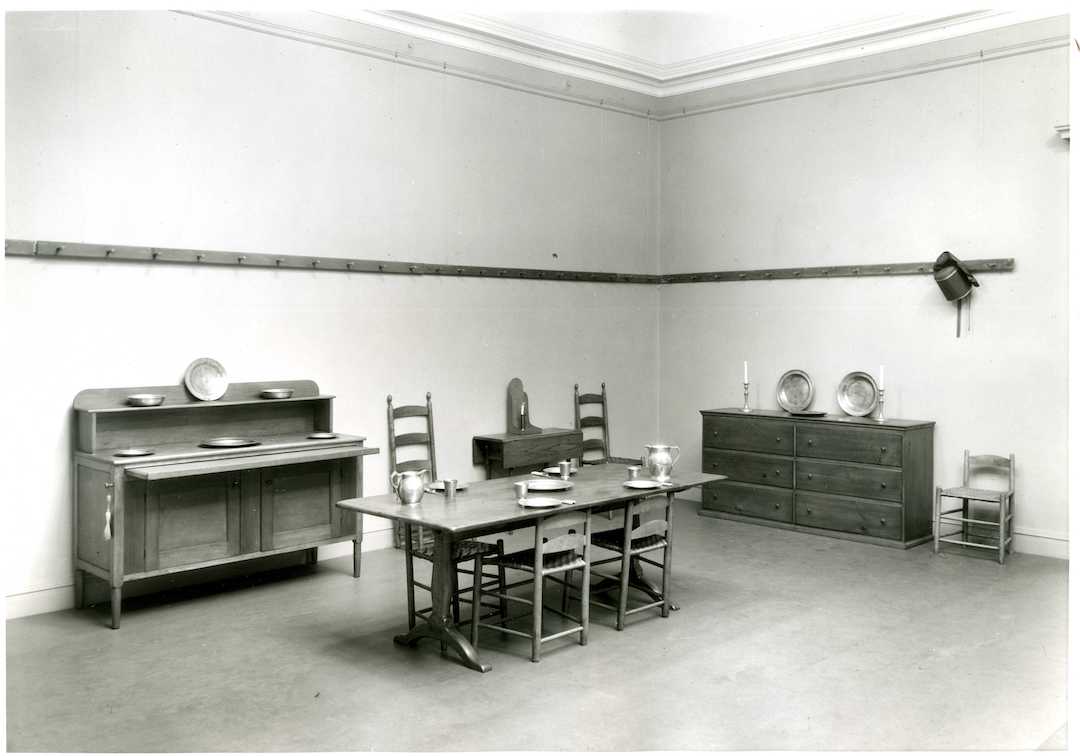

Community Industries of the Shakers, The Berkshire Museum, 1932

In 1932, the Andrewses organized their first large-scale exhibition of Shaker material at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield—an event that introduced their work to a culturally influential audience of writers, artists, museum directors, curators, and preservationists; notably, Juliana Force (1876-1948), director of the Whitney Museum of American Art. This event coincided with the publication of The Community Industries of the Shakers (1932), a historical overview of the Shaker economy focused on New/Mount Lebanon—the first of several books authored by the Andrewses.

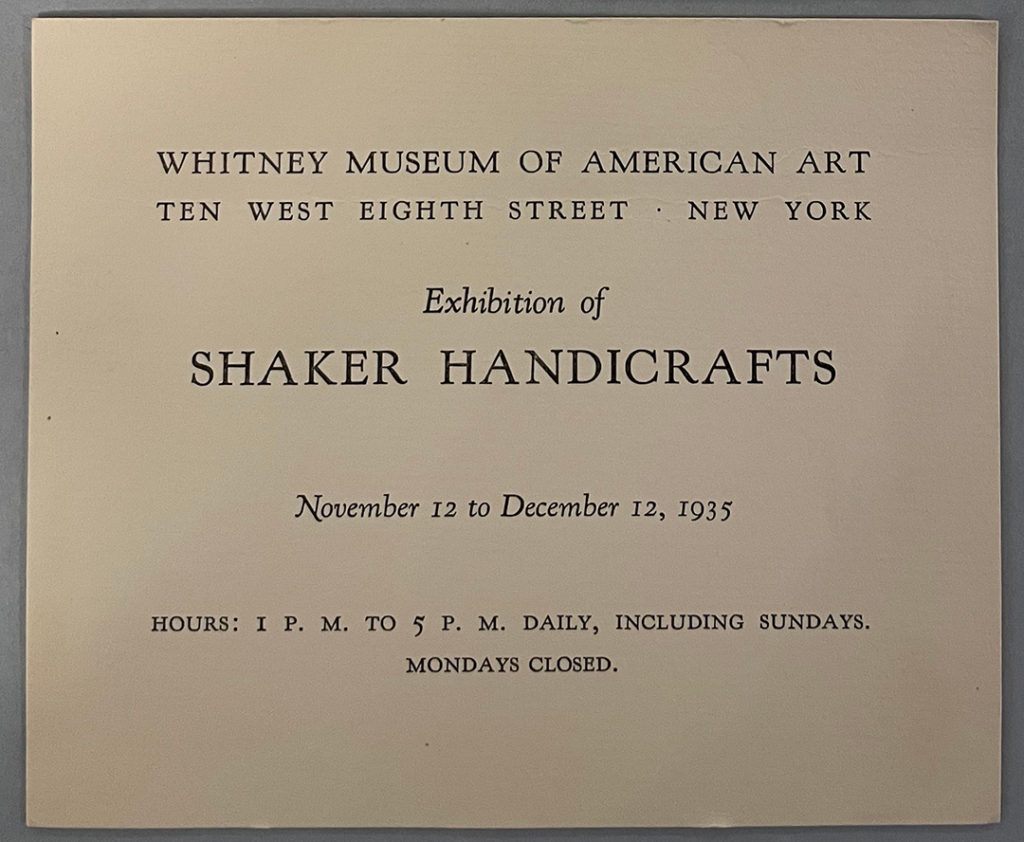

With the support of Juliana Force, the Andrewses mounted Shaker Handicrafts, an exhibition at the Whitney in 1935. Ted and Faith curated the show themselves and were permitted to arrange their collection in whatever way they desired with full institutional support from the Whitney. Faith recalled that this project was, “Christmas all the time… We were running it all.” To the exhibition, the Shakers of Hancock, Massachusetts, lent a watercolor, East View of the Brick House. This important loan demonstrated the support of the living Shakers, which was a first.

The Andrewses had been proselyting the merits of Shaker design and craft amongst New York’s culture brokers for over a decade; however, it was their debut at the Whitney and the support of Juliana Force that led to introductions with important luminaries such as Dorothea Canning Miller of the Museum of Modern Art, Holger Cahill of the Federal Art Project, Edith Gregor Halpert of Downtown Gallery, members the Rockafeller family, artist Charles Sheeler, and others.

In 1937, Ted received a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to further his research on Shaker design and material culture. This, combined with the fiscal support of Juliana Force, precipitated the publication of Shaker Furniture (1937), a book highlighting masterworks of Shaker design from the Andrews collection accompanied by photographs of William F. Winter (1899-1939) staged “in situ” in Hancock’s brick dwelling. The forward was written by Homer Eaton Keyes (1875-1938), founder and editor of the magazine Antiques, who was an unwavering advocate of the Andrewses’ work. (It was an article published by Keyes in 1928 that led Laura Bragg (1881-1978), director of the Berkshire Museum, to present the exhibition of the Andrews collection in 1932, which led to the subsequent introduction to Juliana Force.)

The public attention received by the publications and exhibitions led Ted to draft a “Prospectus for a Museum of the American Shakers,” which proposed the development of a dedicated Shaker museum located next to the Hancock community. This was the first of many ideas, attempts, and failures over the subsequent two decades to establish the future of the Andrews Shaker collection. In 1941, (following the 1940 publication of The Gift to be Simple: Songs, Dances, and Rituals of the American Shakers), the Andrewses petitioned the Smithsonian Institution to accession their collection, only to be declined due to a “lack of space.” The Library of Congress similarly declined, agreeing to take on stewardship of printed materials but not artifacts.

Yale University and Amherst College seemed like strong possibilities, given Ted’s alumnus connection. In the mid-1950s, he sent Yale a prospectus for “The Andrews’ Teaching Collection,” housed in the Yale Art Gallery as a hands-on curricular tool for the university—the American Studies Program in particular. (During this time, Ted also published his third text, The People Called the Shakers (1953), a comprehensive history of the Society—his most ambitious publication to date.) Sadly, Ted’s vision a center of Shaker studies at Yale was a bit too confining to be a reality. The university was unable to dedicate the space within the Art Gallery and Sterling Memorial Library stipulated in the proposal and in 1958, the Andrewses withdrew the offer of their gift.

In the wake of the disappointment at Yale, several other institutions stepped up to court the Andrews Shaker collection. A prime selection of materials was enthusiastically sold to the American Museum in Bath, England, where the Andrewses helped to curate a permanent Shaker display room. Other offers came in from Pleasant Hill Shaker Community in Kentucky, Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, Wesleyan University, Williams College, the University of Illinois, Sturbridge Village, and the Clements Library at the University of Michigan. None of these negotiations moved forward. De Pillis assessed that this is because the “purchasers did not understand that the collection was a unit.” (p. 32)

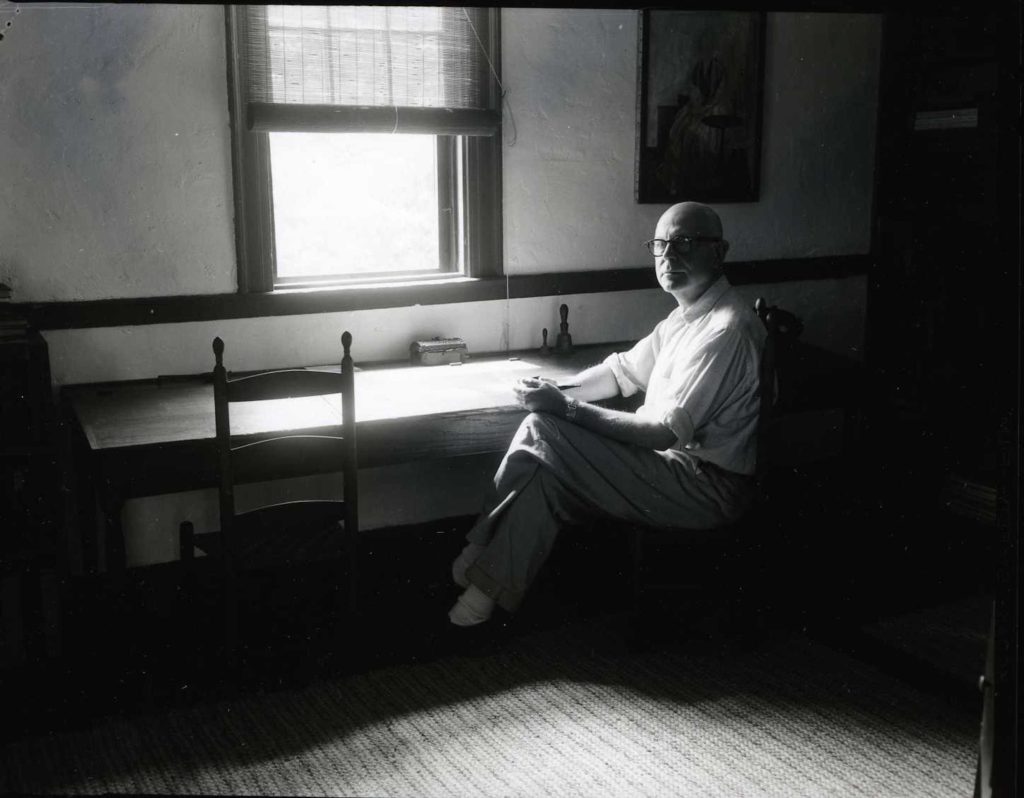

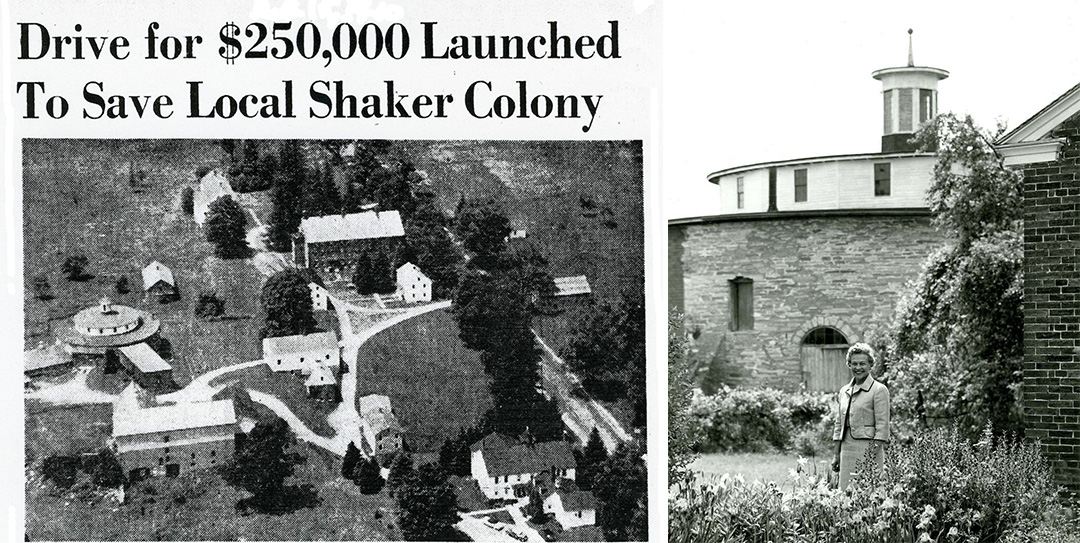

In 1959, fate led Ted and Faith back to where they started: the Hancock Shaker settlement, when a group of dedicated local citizens proposed purchasing the entire village to build a museum. Amy Bess Miller (1912-2003) and her husband, publishing magnate Lawrence K. “Pete” Miller (1907-1991), were at the helm—raising funds, overseeing the restoration, and opening the Shaker Village in July 1961. Ted, after teaching at the Scarborough School in Westchester County, New York, for most of the 1940s and 50s, signed on as the museum’s inaugural curator.

On December 6, 1960, the Andrewses signed an agreement to give their furniture collection to the newly established Shaker Community, Inc. Fortunately, they had the foresight to include a surrender provision clause, stipulating that the donee return all property in the event the Village fail to make proper use of it. (It turned out that, regardless of the clause, the Andrewses could not enforce a complete surrender.) According to De Pillis, disagreements between Amy Bess Miller and Ted Andrews were immediate, openly hostile, and ultimately ruinous—not only for Ted’s employment as curator but also for the future of the Andrews Collection at Hancock. From the outset, Amy Bess wanted to open the Village immediately to cater to summer tourists, whereas Ted wanted to delay opening until exhibits were up to museum standards. They had different priorities and tended to be at odds about most decisions related to exhibitions and historic preservation.

In due course, Amy Bess forced the Andrewses aside, gradually phasing out their involvement from Shaker Community Inc. by demoting Ted, forcing him to resign from the board, and replacing him with another curator who put his own “Plan of Operation” in place. In 1962, unable to withstand the daily persecution, Ted resigned and removed himself from all involvement. (Faith had previously been “fired,” even though she held no official position.) Despite this unsettling turn of events, Amy Bess insisted that the remaining objects from the Andrews Collection promised to the Village be delivered ASAP.

After protracted mediations between the Andrewses and Shaker Community, Inc. regarding the Andrews Collection, the statement in the original 1960 deed of gift—“said collection shall be used, exhibited, displayed, and maintained by the Donee, its successors and assigns, under the direction of the Donor—was interpreted in favor of Hancock. Apparently, under the direction proved too ambiguous for the contract to be terminated. On January 28. 1964, the Andrewses signed a new agreement revoking the first and committing Hancock to publish a catalog of the Andrews Collection “within a reasonable time” and pay a sum of $8,666.66 for the objects—including the collection of Shaker gift drawings—that were already on site.

Despite all setbacks, the two ”collector-scholars” (as Ted and Faith referred to themselves) continued their work. Ted died in Pittsfield on June 6, 1964, and Faith went on to publish Religion in Wood (1966), Visions of the Heavenly Sphere (1969), Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life (1975), and Masterpieces of Shaker Furniture (1999), all of which were credited to Edward Deming Andrews posthumously. Also, in 1965, she successfully negotiated the transfer of the remainder of their Shaker materials—manuscripts, books, and ephemera that she estimated totaled 15% of the Andrews Collection overall—to the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum where it resides as the Edward Deming Andrews Memorial Shaker Collection.

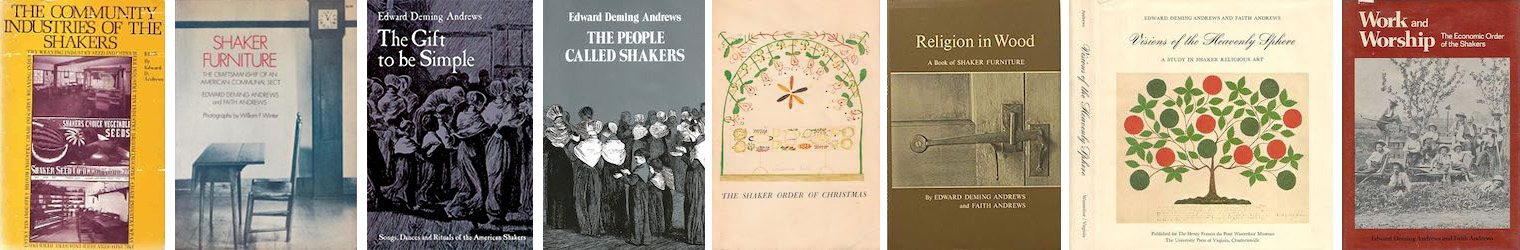

PUBLICATIONS by

Dr. Edward Deming & Faith Andrews

- The Community Industries of the Shakers (1933)

- Shaker Furniture: The Craftsmanship of an American Communal Sect (1937)

- A Gift to be Simple: Songs, Dances, and Rituals of the American Shaker (1940)

- A People Called the Shakers (1953)

- The Shaker Order of Christmas (1954)

- Religion in Wood: A Book of Shaker Furniture (1966)

- Visions of the Heavenly Sphere: A Study in Shaker Religious Art (1969)

- Work and Worship: The Economic Order of the Shakers (1974)

FURTHER READING

Christian Goodwillie and Mario S. de Pillis, Gather Up The Fragments: The Andrews Shaker Collection, (New Haven/London: Yale University Press), 2008.

William D. Moore, Shaker Fever: America’s Twentieth-Century Fascination with a Communitarian Sect, (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press), 2020.

Oral History with Faith Andrews, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, 1982.

MUSEUMS FEATURING THE ANDREWS SHAKER COLLECTION