The Philadelphia Shaker Community: An Outpost of Motherly Love

– April 2024 –

The Philadelphia Shaker Society is often overlooked within the overall arc of Shaker history. Perhaps this is because the Philadelphia settlement was a short-lived experiment that lasted only 50 years, operating as an offsite “out family” of the Watervliet community from 1858 to 1908. Or, maybe it is because records of the Philadelphia outpost are scant. Few written accounts survive—what we do know comes from letters retained by other branches of the Society, and the Philadelphia Shakers were not furniture makers or craftspeople, so material culture is not a tangible tether to the lives and experiences of Philadelphia’s extraordinary Believers.

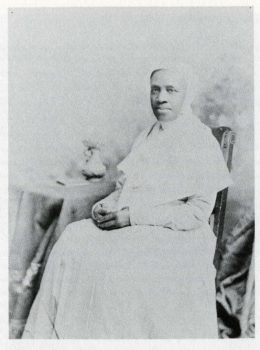

As a predominantly Black, working-class, urban utopia founded by the visionary, female spiritual leader Mother Rebecca Cox Jackson (1795-1871), the significance of the Philadelphia Shaker community cannot be understated. The Philadelphia Believers actualized the formative ideals of racial and gender equity, integrating Shakerism into everyday life in a profoundly meaningful way that any other branch of the Society could not replicate.

Rebecca Cox Jackson (1795-1871) was born in Philadelphia to a free family of African American descent. Tragedy pervaded her early years. From infancy, Rebecca was raised by her grandmother until, at age two or three, she was transferred to the care of her mother, Jane Wisson (or Wilson), and her stepfather, a sailor. Nothing is known of her biological father, who was most likely deceased. When Rebecca was six, her stepfather died at sea. The following year, her much-beloved grandmother also died and, by the time she was ten, Rebecca was living in a Philadelphia apartment with her mother, younger sister, and infant brother—the presumed offspring from a third marriage. The death of her mother followed just a few years later when Rebecca was 13.

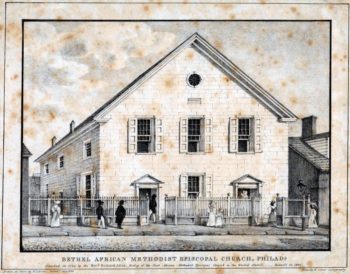

From her mother’s death in 1808 until the opening of her autobiography in 1830, very little is known of Rebecca’s life. At some point, she was taken in by her brother Joseph Cox (1778-1843), who was considerably older and figured prominently in Rebecca’s life and writings. Joseph was a pillar of the powerful Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church of Philadelphia, serving as a preacher and elder in addition to a variety of church-related offices. Rebecca continued living in her brother’s household after marrying Samuel S. Jackson, (they had no children). She worked as a seamstress and, seemingly, lived a life of relative prosperity and safety.

Rebecca’s earliest writings illustrate a fear of sudden, irrational physical violence, which may have stemmed from her traumatic personal history as well as the growing racial tension and violence inflicted on Black Philadelphians by white mobs in the 1830s and 40s. Black-owned homes were destroyed and her brother’s Bethel A.M.E. Church was damaged.

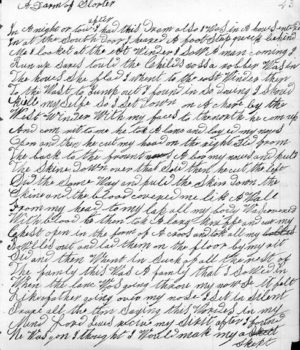

It was in july July 1930, at age 35, that Rebecca experienced a spiritual conversion. The event happened during a severe thunderstorm which, coincidently, was one of her deep-set fears. “In time of thunder and lightning I would have to go to bed because it made me so sick,” she wrote in her journals, (pictured right, in the collection of the Berkshire Athenaeum, Pittsfield, MA). During the storm, Rebecca heard an inner voice assuring her that she was going to die and go to hell. Very quickly, she was struck by the divine realization that “the messenger of death, was now the messenger of peace, joy and consolidation.” She began praying for the merciful forgiveness of her sins and, at the time of conversion, which she likened to a cloudburst, she felt a flood of love for God and humankind and her phobia vanished.

Soon thereafter, Rebecca began having visions of a divine inner voice that instructed her to heal the sick, convert the sinful, and converse with angels. It became a voice of instruction and protection, and she refused to go anywhere or do anything without the explicit guidance of the voice. Her early writings describe Rebecca’s efforts to learn to hear clearly and obey absolutely. In many ways, her visionary experiences were an exercise in practice and control, facilitated by an ascetic regimen of fasting, weeping, praying, and sleep deprivation that kept “her spirit eye clear.”

Following a revelation about lust, sin, and the fall of man, Rebecca began practicing celibacy. She persuaded her husband that her body was no longer hers or, more pointedly, his; rather, it was an instrument of the divine spirit that inhabited her. Eventually, her ascetic lifestyle became problematic to her household. “My dreams became a burden to my family,” she wrote. “I had started to go to the promised land, and I wanted husband, brother and all the world to go with me, but my mind was made up to stop for none.” She established herself as a leading member of a “Covenant Meeting” comprised of A.M.E congregants believing in Perfectionism before starting her own weekly meeting co-led by her spiritual sister Mary Peterson, wife of A.M.E preacher Daniel Peterson. These meetings began to attract large crowds, setting off a revivalist fervor within the small towns and villages west and south of Philadelphia.

In 1836, Rebecca separated from her husband and left Philadelphia, setting out on the road as an itinerant preacher with her Perfectionist group, The Little Band. When proselytizing in Albany, she observed a Shaker meeting in Watervliet. In her journal, Rebecca recalled:

“When they came in, the power of God came upon me like the waves of the sea… For the first time I saw a people sitting and looking like people that had come into a place prepared for the solemn worship of the true and living God, who is a spirit and who will be worshiped in spirit and in truth. This people looked as though they were not of this world, but as if they were living to live forever.”

Following her initial introduction to Shakerism, Rebecca returned to the road to continue her work as an itinerant preacher. In her journals, she seems to struggle with conflicting desires for her own autonomy and the support of a spiritual community. For two winters from 1841 to 1843, she and The Little Band resided in Albany in the communal Perfectionist home of the Ostrander family. After two visits to the Shaker community in 1843, many members of Rebecca’s group joined the Shakers and, after a vision-fueled three-day visit, she expressed a total commitment to the faith.

The general holy appearance of the Shakers appealed to Rebecca—she praised their comportment, uniformity, plainness, cleanliness, and otherworldly spirituality. She wrote that they struck her as the living embodiment of Christian perfection, and the values and beliefs of Shakerism were uncannily similar to her own. Although she did not explicitly address the Shaker practice of racial equality in her journals, it’s plausible that the community’s inclusion of Black Believers and commitment to abolitionism was further enticement to join.

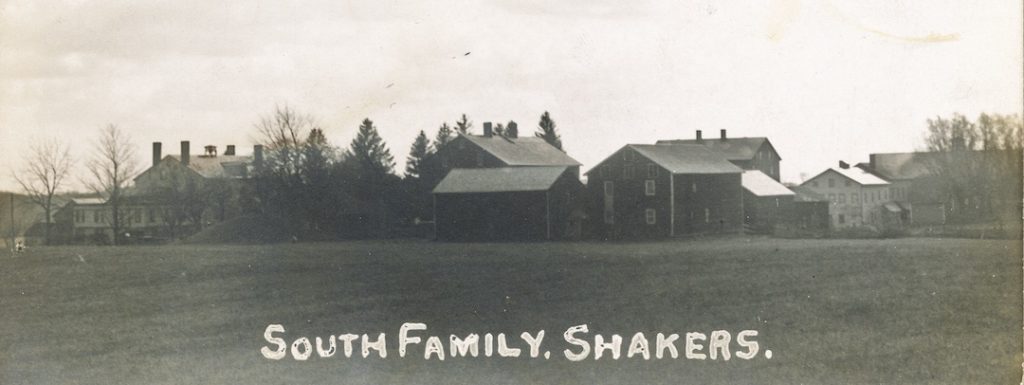

Despite her conversion to Shakerism, Rebecca returned to Philadelphia, and it wasn’t until 1847 that she officially took up residence in Watervliet with her disciple, Rebecca Perot (1833-1913). The two Rebeccas were permitted to stay together, residing in the same retiring room as members of the South Family for approximately four years. The records from this time are scarce; however, there is documentation of Rebecca Cox Jackson’s work as a seamstress, (perhaps drawing on her previous experience), with regular stints in the kitchen as an assistant cook, or “kitchen sister.”

Although rank-and-file members did not generally preach at Meetings, Shaker leadership recognized Rebecca’s abilities and permitted her to preach at Sabbath Meetings open to the public. A Shaker record from September 10, 1848, notes, “Sister Rebecca Jackson rose up and spoke beautiful of the way of God.”

From her earliest days in Watervliet, Rebecca expressed concern about her alienation from the world. She reflected, “I wondered how the world was to be saved, if Shakers were the only people of God on the earth, and they seemed busy in their own concerns, which were mostly temporal.” Soon thereafter, her concern was acutely pointed toward the “spiritual and temporal bondage” of Black America—enslaved and free. From October through December of 1850, the two Rebeccas were sent to Philadelphia on a missionary tour, presumably to convert young, Black Believers to join the faith. Upon returning to Watervliet, Rebecca Cox Jackson proclaimed that she had received a calling to establish a permanent Shaker mission in her hometown.

Eldress Paulina Bates (1806-1884) refused to authorize Rebecca’s plan. In the Eldress’s view, a Philadelphia settlement would create too much exposure to the false values and corruptions of the world. Shaker communities were designed to be socially isolated and economically self-sufficient—only limited, sanctioned business relationships were permitted between Shakers and non-believers. In Rebecca’s view, the Eldress was standing in the way of a divine project. She described this disagreement as a conflict between her “inward” (divine) lead and her “outward” (Shaker) lead.

Eventually, the two Rebeccas left Watervliet for Philadelphia in July 1851. Shaker leadership recorded that Rebecca “abandoned her home in Zion” to set out on a mission to convert the nation, “perhaps consciously, but I should say, rather delusively,” wrote Elder David A. Buckingham (1803-1885). In 1854, Rebecca reflected on her departure from Watervliet and subsequent estrangement from her fellow Believers, writing about her continued bewilderment over the Elders’ failure to approve her mission and, so doing, connect with potential Black converts. During this six-year stint in Philly, the Rebeccas became interested in spiritualism, participating in seances and training as mediums. Ultimately, Rebecca Jackson could not shake her connection to Shakerism. She saw herself as the only Believer capable of practicing the Shaker gospel in a truly nonracist manner in which Black Shakers and white Shakers could share a communal life, and she and Rebecca Perot returned to Watervliet for one final year of residence among their Brethren and Sisters.

In October of 1858, the Rebeccas left Watervliet with a blessing from Eldress Paulina Bates and the moral, legal, and financial backing of all nineteen Shaker settlements to start a new branch of the Society in Philadelphia. The following year, on the eve of the Civil War, the Philadelphia Shaker community was gathered, and Rebecca Cox Jackson became Mother Rebecca. The Philadelphia Shakers did not exceed twenty members with membership comprised of mostly Black women who worked as domestics, laundresses, or seamstresses. Documentation of the community’s members, activities, and even their whereabouts is scarce, but there is evidence tying them to the addresses 724 Erie Street in North Philadelphia and 522 South 10th Street in Washington Square, (the location of an ACME Market today).

Sadly, Mother Rebecca recorded very few journal entries after 1858; her final entry is dated June 4, 1864. Even so, evidence suggests that the two Rebeccas continued to preach and practice Shakerism in Philadelphia, gaining enough of a presence within the established religious landscape to warrant mention in W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1899 publication, The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, in which Du Bois documented two Shaker families in Philadelphia’s historically Black seventh ward.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, members of the Mount Lebanon and Watervliet ministries would visit the Philadelphia community for weeks at a time, and accounts of these visits confirm that the Philadelphia society remained in union with the Shaker ministry. In 1872, a group from Watervliet described the Philadelphia townhouse as “almost palatial” with fully modernized amenities like plumbing and central heat. They recorded, “a large drawing room, sufficient for twenty souls to sit down,” and a carpeted meeting room with “marble mantles… very nice, almost extravagantly so.” Recounting a worship service, the visitor described the religious exercises as “beautiful and zealous… When they attempt to shake, they get right down, almost to the floor, and bow, bend, and strip off pride and bondage.” In 1873, Elder Henry Clay Blinn (1824-1905) of the Canterbury ministry agreed, noting the Philadelphia Believers seemed “to understand the object of their calling & were resolutely determined to abide faithful.”

Mother Rebecca Cox Jackson died at age 76 on May 24, 1871, and she was buried in the Shaker cemetery in New Lebanon, New York. Later, her body was moved to Eden Cemetery, a historically Black cemetery near Philadelphia. Following the loss of her spiritual Mother, companion, and Elder, Rebecca Perot assumed leadership of the sect as well as the name “Mother Rebecca Jackson” and, thus, the two Rebeccas became one. The second Mother Rebecca continued to lead the Philadelphia Shakers for over 25 years until, in the 1890s, membership began to decline. In 1896, four of the remaining Philadelphia Sisters—including the self-anointed Mother Rebecca Jackson (nee Perot)—moved to Watervliet; however, it is uncertain if the Philadelphia society was closed at that time. Upon Mother Rebecca (Perot’s) return to Watervliet, Brother Alonzo Hollister (1830-1911) recorded, “I believe this ends Mother Jackson’s colony in Philadelphia.” Immediately following this first note is an amendment: “I have learned since, there is still a colony of Believers there, and zealous too. 1908.”

At this point, the fate of the Philadelphia community remains unknown. Mother Rebecca (Perot) died in 1901 at age 82. She is buried in the Shaker cemetery in Watervliet.

Works Cited:

Jean McMahon Humez, Gifts of Power: The Writings of Rebecca Cox Jackson, Black Visionary, Shaker Eldress (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1987)

Lorraine Weiss, “A Determinded Voice: Mother Rebecca Cox Jackson,” Shaker Heritage Society (January 21, 2021)

Whole Lot of Shaker Going On: The 1930s in South Salem, New York

– February 2024 –

On Spring Street in South Salem — just a stone’s throw from John Keith Russell Antiques — sits an eighteenth-century farmhouse named “Shaker Hollow.” The classic, two-story Colonial with a gable roof, central chimney, and clapboard exterior was built in 1795 by James Conklin (1749-1806), a prosperous farmer, landowner, and distiller of rum and cider brandy. Generations of Conklins lived on Spring Street until, in 1928, the farmhouse was sold to Juliana Force (1876-1948), an aptly named powerhouse of the New York art world. It was Force who named the Conklin home “Shaker Hollow” in honor of her collection of Shaker furniture, which was displayed in the south wing of the house. (According to local lore, the addition was built for that purpose.)

Force was originally from Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In 1907, she was hired to assist with the affairs of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942), a New York-based heiress, sculptor, and patron of the arts. In 1918, Whitney founded the Whitney Studio Club in Greenwich Village and, under Force’s direction, the Club became an important forum for artists to connect and explore emerging themes in contemporary art.

Operating as a membership-based organization, the Club offered many amenities, including an exhibition space, squash court, library lined with art books, salon with blue satin curtains, and billiards room. Force maintained an apartment above the Club that, like her primary residence in Bucks County, she decorated with outdated Victorian furniture, Americana, and modernist art — an eclectic amalgamation that became her signature and much-celebrated style.

Force’s close friend and neighbor in the Whitney Studio Club building was artist Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) who, incidentally, shared her affinity for American antiques. To his biographer, Constance Rourke, Sheeler articulated:

“I don’t like these things because they are old but in spite of it. I’d like them still better if they were made yesterday because then they would afford proof that the same kind of creative power is continuing.”

In February 1924, artist Henry Ernest Schnakenberg (1892-1970) organized Early American Art, an exhibition at the Whitney of contemporary American Modernism alongside early American folk art — both Sheeler and Force lent pieces of Americana to the show. The New York Times called the exhibition “funny and quaint,” remarking on the engaging connections between art and antiques. For example, Sheeler’s painting, Portrait of a Woman (1924), was shown in dialogue with a chalkware cat.

Radically imaginative for the time, Early American Art illustrates the desire to forge a new trajectory of American art, connecting the work of contemporary artists to early American traditions — a legacy that would stand in contrast to Europe. Force, as a proponent of Modernism and Americana, became a figurehead of this new movement. Robert Bishop, former director of the American Folk Art Museum, wrote that Force, “did not view folk art as a minor expression of American art, but an extension of craft traditions in the realm of fine art.” Force’s biographer Avis Berman concurs, writing that Early American Art was a “manifestation of the indigenous American culture that [Juliana] and Gertrude were working so assiduously to legitimize… The folk artists offered a historic alternative to academic training; the Whitney galleries, where young and emerging artists could exhibit, provided a contemporary alternative to the Academy.”

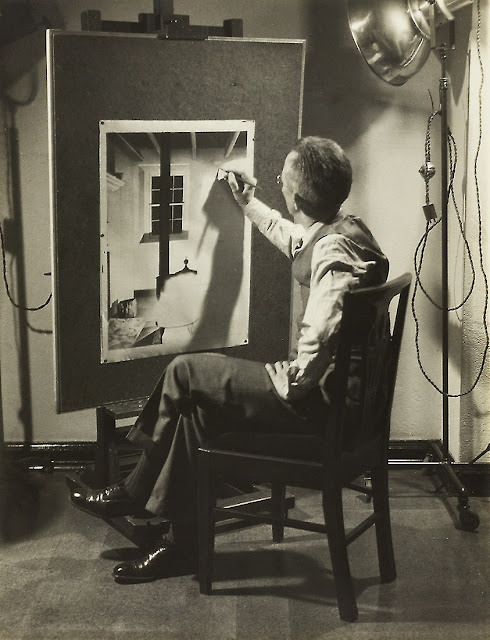

Charles Sheeler, Whitney Studio Club interiors, c. 1925-1926, Whitney Museum of American Art

Around this time, Sheeler began acquiring Shaker objects, buying materials directly from the Shaker communities in New Lebanon and Hancock, and working with a trusted dealer. By 1926, he had cultivated an important collection, which furnished a cottage that he and his wife Katherine rented in South Salem — “a charming stucco studio, where the antiques of Pennsylvania Dutch and Shakers… mingle in agreeing medley with modernist furniture,” described by poet William Carlos Williams (1883-1963). Selections of the Sheelers’ Shaker furniture and collectables were documented in a series of photographs that Sheeler shot in 1929. Today, these photos of South Salem are important artifacts that not only illustrate how Sheeler lived with Shaker, but further, provide some insight into his creative process.

Though best known for his precisionist painting, Sheeler launched his career as a commercial photographer and, ultimately, the camera became his primary research method for his painting practice.

“Photography is nature seen from the eyes outward, painting from the eyes inward,” Sheeler wrote in his unpublished autobiography (1937). “Photography records inalterably the single image while painting records a plurality of images willfully directed by the artist. I have never seen in any painting the fleeting glimpse into a person’s character that I have seen depicted in some photographs, nor have I seen in any photograph the full rounded summation of the character of an individual that a Rembrandt or Greco portrays.”

The 1929 South Salem photographs subsequently became the artist’s “American Interiors” series of paintings, comprised of four related works: Interior (1926), Home, Sweet Home (1931), Americana (1931), and American Interior (1934). Each artwork features objects from Sheeler’s Shaker collection prominently within the composition; for example, the long Shaker table and bench with arch cutout feet (appearing in Home, Sweet Home, Americana, and American Interior), the two Shaker workstands — one with a tray top (in American Interior and Interior), and the unmissable oval pantry box (in American Interior and Americana). Looking at the photographs, it seems that Sheeler was interested in the visual confusion of three-dimensional objects flattened by the camera’s lens. The paintings, in turn, explored the affect of that confusion.

Charles Sheeler, left: Interior (1926, Whitney Museum of American Art),; center: Home, Sweet Home (1931, Detroit Institute of Arts); right: Americana (1931, Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The final painting in American Interiors, American Interior, is credited as the most masterful in the series. It was painted in 1934 following the tragic death of Katherine, who succumbed to cancer in 1933. In the wake of his wife’s passing, Sheeler described his home as a place that had “come to hold something of the qualities of a cloister. These four walls are near to being the boundaries of my world.”

Flattened, compressed, and abstracted, American Interior’s composition feels like a world unto itself. The furniture, patterned floor coverings, and objects merge in the picture plane in a style that evokes Cubism, but with an entirely American subject matter. Despite the visual chaos of the scene, Sheeler depicts an agreeable clutter — even a coziness. Indeed, American Interior is rendered with an efficiency, harmony, and precision that not only conveys an affection for his South Salem home, but further, expresses a sense of clarity — a lack of superfluidity — that mirrors the Shaker furnishings therein.

Left: Charles Sheeler, South Salem interior, 1929; Right: Charles Sheeler, American Interior (1934, Yale University Art Gallery)

Some art historians have questioned if Sheeler’s depiction of antiques is an interrogation of the culture of collecting that was popularized during the interwar years. The 1920s and 1930s witnessed an upsurge in the American folk art market, as well as the “colonial revival” in architecture and design, and the opening of period rooms in major national museums. Consuming, reviving, and exhibiting artifacts was a more visible phenomenon. This elevation of humble objects to contemporary masterpieces cultivated a patina of preciousness around the material culture of the past — a tactic to re-present history and, so doing, reframe the present.

The paintings of the American Interiors can be encountered like period rooms — exhibits that celebrate beautiful objects while also nodding, ironically, to their commodification and contrivance. Too, they have a memorial-like quality — a reverence that honors the objects’ significance in Sheeler’s life as well as their history more broadly.

Berman opines, (via art critic Forbes Watson), that it was Sheeler’s appreciation of Shaker design that encouraged Force to acquire a collection of her own. The spare, utilitarian aesthetic appealed to her—she reverently separated Shaker artisans from folk painters, always citing the “elegance” of Shaker design and craftsmanship. In 1928, just two years after the Sheelers moved upstate, Force purchased the nearby Conklin farmhouse, naming it “Shaker Hollow” in honor of her burgeoning interest and enduring friendship. Force and Sheeler were neighbors once again, this time sharing a street in a small Westchester hamlet as opposed to a hallway in Greenwich Village.

Unlike the Sheelers, Force was only in South Salem part-time as her work kept her engaged in New York. In 1929, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney offered her collection of more than 600 works of American art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) with a promised gift of five million dollars to build and endow a new wing to exhibit it. The MMA declined her offer, so she decided to establish her own museum with Force at the helm as the founding director. The Whitney Museum of American Art opened on November 18, 1931, in a rowhouse on West Eighth Street near Fifth Avenue. Force later reflected, “It was decided that what was most needed was an organization unhampered by official restrictions but with the prestige which a museum invariably carries—an organization which would exhibit and purchase under the most auspicious circumstances native works of art.”

In its formative decades as an institution, the Museum presented works from the margins of art history — stories that had been ignored, buried, or forgotten — as a way to link contemporary art to a uniquely American past. Shaker, as an unrecognized bastion of American individualism and creative culture, fit perfectly within this objective. According to Sheeler:

“The Shaker communities, in the period of their greatest creativity, have given us abundant evidence of their profound understanding of utilitarian design in their architecture and crafts…It is interesting to note in some of their cabinet work the anticipation, by a hundred years or more, of the tendencies of some of our contemporary designers toward economy and what we call the functional in design.”

In the early twentieth century, the role of Shaker design as an early form of vernacular American design was just beginning to be explored, and Force was eager to bring this important historic material to New York.

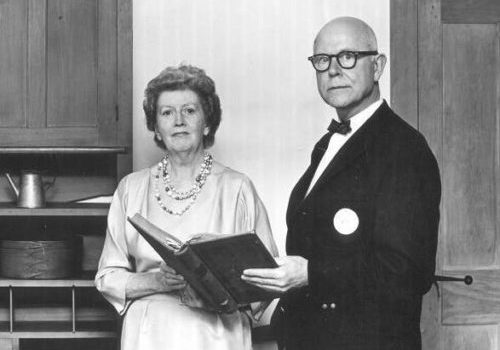

Dr. Edward Deming “Ted” (1894-1964) and Faith Andrews (1896-1990), renowned collectors, scholars, and advocates of Shaker material culture, crossed paths with Juliana Force in 1932 around the opening of their first large-scale Shaker exhibition at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Starting in the 1920s, the Andrewses assembled a vast collection of Shaker material — spanning furniture, domestic objects, tools, garments, visionary artworks, and manuscripts — that they sought to study, preserve, and disseminate to a broad audience. The Berkshire Museum show, (facilitated by the visionary museum director Laura Bragg), provided entrée to the New York art world—an intelligent, successful, and well-connected group that would prove essential in the advancement of the Andrewses’ project.

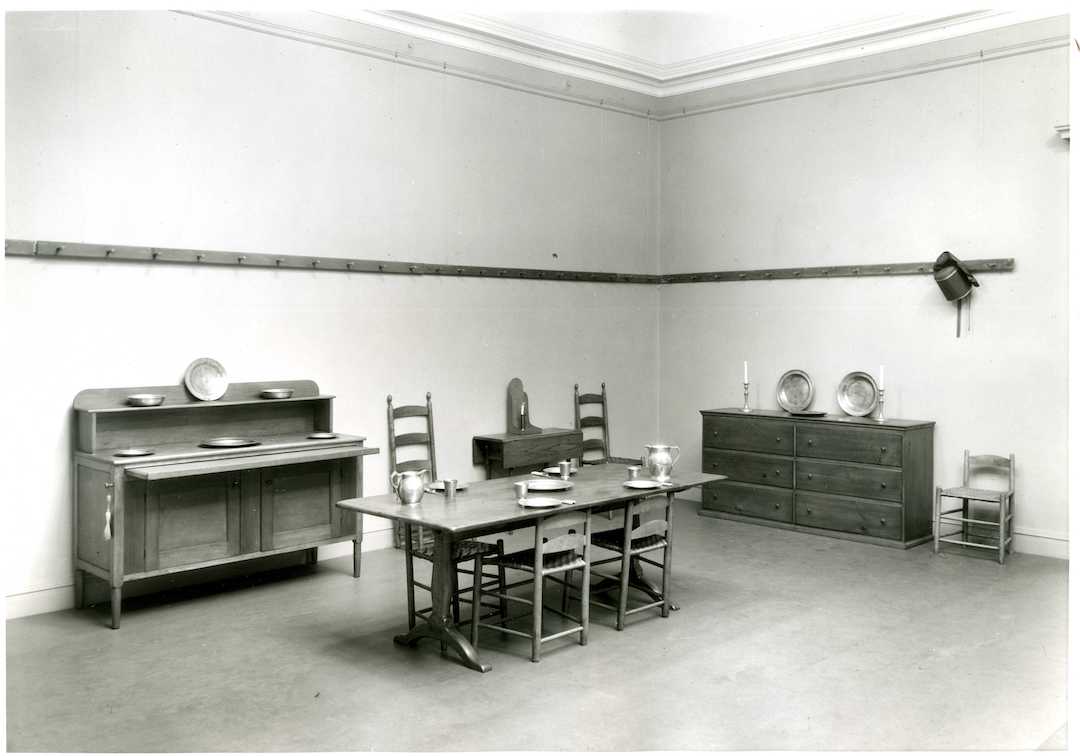

Community Industries of the Shakers, installed at the Berkshire Museum, 1932

Following the Berkshire Museum exhibit, Force traveled to Pittsfield to meet with the Andrewses and tour Hancock and Mount Lebanon Shaker villages. “Juliana Force was like Alice in Wonderland,” recalled Faith. “She saw what this was in a glance and knew it had to be shown as a special contribution to American culture.” In November 1932, they began planning an exhibition at the Whitney, Shaker Handcrafts, which opened November 12, 1935. Ted and Faith curated the show themselves and were permitted to arrange their collection in whatever way they desired with full institutional support from the Whitney. Faith recalled that this project was, “Christmas all the time… We were running it all.”

The Andrewses had been proselyting the merits of Shaker design and craft amongst New York’s culture brokers for several years; however, it was their debut at the Whitney and the support of Force that led to introductions with other luminaries such as Dorothea Canning Miller of the Museum of Modern Art, Holger Cahill of the Federal Art Project, Edith Gregor Halpert of Downtown Gallery, members of the Rockefeller and Vanderbilt families, and, of course, artist Charles Sheeler. Although her own finances were notoriously in disarray, Force contributed one thousand dollars to the publication of Shaker Furniture (1937), a book highlighting masterworks of Shaker design from the Andrews collection accompanied by the photographs of William F. Winter (1899-1939) staged “in situ” in Hancock’s brick dwelling.

Nicknamed “Mrs. Fierce,” Force’s hallmarks were her impetuous generosity and extravagance — Shaker Hollow was just one of five houses between Europe and the US that she could not afford. Starting in 1932, the Andrewses and Force maintained a relationship rooted in their shared appreciation of Shaker material. The couple helped deepen Force’s understanding of Shaker history and design, advising on new acquisitions for her collection.

In the years following the exhibition at the Whitney, the relationship between Force and the Andrewses began to fall apart — in large part due to Force’s financial woes. In the spring of 1937, the Andrewses cataloged Force’s Shaker Hollow collection — 42 pieces of furniture in all, which was offered at a private sale in May. Gallerist Edith Halpert (1900-1970) brokered the sale to Blanchette Rockefeller (1909-1992) for $10,000, arranging for delivery of the furniture to the Rockefeller estate in Pocantico, New York. “No similar collection can ever be assembled as this — with few exceptions — represents the cream of the Shaker tradition,” wrote Halpert.

The Shaker Hollow sale was what provided funds for Shaker Furniture so, ultimately, it was a positive for the Andrewses. The incident that caused irreparable damage occurred later that fall and related to the Andrewses’ collection of Shaker visionary artworks, or “gift drawings.” Previously, the Andrewses asked to store the gift drawings in the vault of the Whitney Museum to keep them out of the fray while the Federal Art Project came to their home to document Shaker design. The artworks were securely housed at the museum until the Shaker Hollow sale in May, when they were returned to the Andrewses.

In January of 1938, a string of confusing correspondence called the ownership of this important collection into question. Essentially, Force’s secretary, Miss Freeman, wrote the Andrewses to inquire about the location of the gift drawings, given that the artworks “belonged to Mrs. Force” and had been unaccounted for since May. Faith kindly responded correcting the ownership of the artworks and confirming that they had been returned to their home in Richmond, Massachusetts.

On February 8, a reply came from Miss Freeman asserting that, in exchange for subsidizing the publication of Shaker Furniture, “Mrs. Force sincerely believes that these drawings are her only tangible result of her large investment.” Never planning on relinquishing the drawings, Ted writes a letter directly to Force inviting her to an in-person meeting to clarify the ownership of the artworks. In response, Force writes that Faith’s previous letter made their ownership clear, which signaled the end of the contentious salvo.*

Andrewses’ biographer Mario S. De Pillis interprets the exchange as Force attempting to strongarm the Andrewses into giving her the gift drawings by wielding an entirely unfounded claim. Regardless, the falling out effectively terminated the most important affiliation that the Andrewses had obtained. Force’s patronage helped raise the visibility of their work and canonize Shaker design within mainstream American cultural history in a significant way.

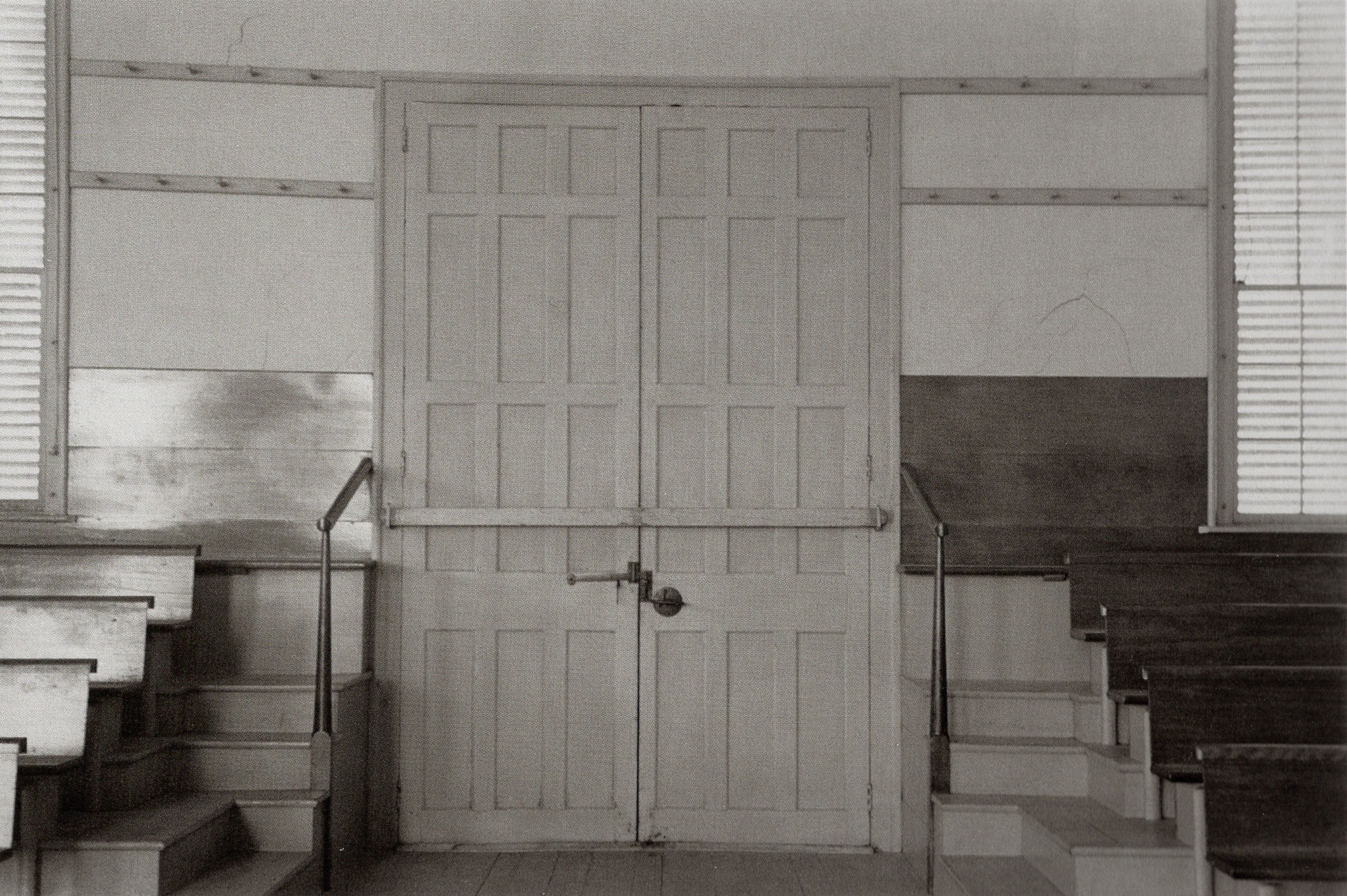

Charles Sheeler, interiors of the Shaker Meetinghouse, Mount Lebanon, NY, 1934

Charles Sheeler did not stay in South Salem long — in 1932, he and his wife moved to Ridgefield, just across the border in Connecticut. Unlike Force, Sheeler managed to hang on to his Shaker furniture and materials until he died in 1965, after which, the collection was acquired by the newly founded Hancock Shaker Village (Pittsfield, MA), where it can be seen today. Force retained ownership of Shaker Hollow until July 1944 when it was sold. (Following an incident with her Nazi-affiliated staff in 1940, Force stopped going to South Salem with any frequency, but that’s another story.) The house was subsequently sold to Herbert Smith, food editor of the New York Herald, who opened the Shaker Hollow Inn restaurant, tearoom, and bed and breakfast. In 1957, the property was sold again to artist Axel Horn (1913-2001), and it has remained in private hands since he died in 2001.

Juliana Force died in 1948, but her legacy — as well as the legacy of Shaker Hollow — endures in South Salem to this day.

* Some accounts of this controversy portray it as much more acrimonious, culminating with a phone call in which Miss Freeman shouts: “We must have the drawings!” The summary relayed here relies on the excellent research based on primary source materials of Mario De Pillis in his essay, “The Edward Deming Andrews Shaker Collection: Saving a Culture,” in Gather Up The Fragments, p. 24-27.

Works cited:

Avis Berman, Rebels on Eighth Street: Juliana Force and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York: Atheneum, 1990)

Mario S. De Pillis and Christian Goodwillie, Gather Up The Fragments: The Andrews Shaker Collection, (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2008)

Howard Devree, “A VITAL MEMORIAL; The Whitney Museum Calls its Exhibition ‘Juliana Force and American Art,’” The New York Times, September 25, 1949, p. X9

Martin Friedman, “The Art of Charles Sheeler: Americana in a Vacuum,” Charles Sheeler, (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968), p. 33-58

Martin Friedman, Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, Photographs, (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1975)

Karen E. Haas, “’Opening the Other Eye’: Charles Sheeler and the Uses of Photography,” The Photography of Charles Sheeler: American Modernist (Boston: Bullfinch, 2002)

William D. Moore, Shaker Fever: America’s Twentieth-Century Fascination with a Communitarian Sect, (Amherst/Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2020)

William D. Moore, “’You’d Swear They Were Modern’: Ruth Reeves, the Index of American Design, and the Canonization of Shaker Material Culture,” Winterthur Portfolio, (Vol. 47, No. 1, Spring 2013), p. 1-34

Lindsay Pollock, The Girl with the Gallery: Edith Gregor Halpert and the Making of the Modern Art Market (New York: PublicAffairs, 2006)

Constance Rourke, Charles Sheeler: Artist in the American Tradition, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1969)

Charles Sheeler, 1937 Unpublished Autobiography, The Photography of Charles Sheeler: American Modernist (Boston: Bullfinch, 2002)

Cynthia Magriel Wetzler, “200-Year-Old House Reveals Some of Its Past,” The New York Times (Feb. 18, 1996)

Kristina Wilson, “Ambivalence, Irony, and Americana: Charles Sheeler’s ‘American Interiors,’” Winterthur Portfolio, (v. 45, no. 4, winter 2011)

Images:

The Whitney Museum of American Art

The Smithsonian Archives of American Art

Yale University Art Gallery

Detroit Institute of Arts

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Art Institute of Chicago

Westchester County Historical Society

The Berkshire Museum

Hancock Shaker Village

Thank you to Maureen Koehl, Town Historian, Lewisboro, New York, for your assistance in identifying the Sheelers’ South Salem cottage, as well as for your excellent article in the Lewisboro Ledger (2015)!

Curiously Inscribed: A Shaker Oval Box with Remarkable Provenance

– December 2023 –

There is a certain unpredictability that accompanies dealing in Shaker. We never know the materials that may come our way through a referral, email inquiry, or auction listing. Over the past forty-some years, John has learned to stay open and responsive—always expecting the unexpected. The capricious nature of the business is a source of both delight and frustration. When we’re looking for tables, you can guarantee we’ll find only chairs. Year-to-year flows of Shaker materials have curious peaks and ebbs, and it’s best not to commit yourself to predictions or assertions as, chances are, someone has made other plans.

In the curious spirit of the antiques world, 2023 has seen a great quantity of excellent Shaker boxes come into our South Salem shop. In late July, our inventory surpassed over 75 Shaker oval boxes. This included the Watt & Jan White Collection, an unrivaled grouping of more than 40 painted Oval Storage Boxes presented at Antiques in Manchester. This followed a three-day box-stravaganza at Enfield Shaker Museum’s annual Shaker Collectors’ Weekend, where participants dove into the minutiae of oval, dovetailed, and seed boxes with a fantastic roster of presenters including Jerry Grant, Christian Becksvoort, Erika Sanchez Goodwillie, Alexandra A. Kirtley, Tom Queen, and others.

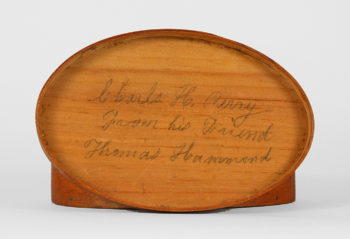

Now in December, we’ve recently acquired a truly unique example of a Shaker oval box that we’re eager to share here: what we believe to be perhaps the only Oval Storage Box positively attributed to the Harvard, Massachusetts, Shaker community.

This box is of classic construction measuring 5 ½ inches across with a pine top and bottom, maple bentwood sides, and copper rivets and brads. Compared with other boxes made by other Shaker communities, the tack pattern is a bit excessive with seven tacks fixing each of the lappers on the base in a four-two-one pattern. File marks can be seen on the surface of the copper—a characteristic shared by oval boxes of the New Hampshire Bishopric, and visible scribe lines run vertically connecting the lines of tacks.

Originally, the box was finished in a pale red wash that has aged to appear like a natural stain and varnish surface. The fingers of the box, which appear to have been traced and cut using a mold, are clipped at the very end in 45-degree angles at the top and bottom to create a rounded effect. The marks from the maker’s blade are still visible in six clumsy bevels—not a common decorative embellishment, but not an unprecedented decision either.

Perhaps most compelling is an inscription in graphite on the interior of the lid that reads:

Charls [sic] H. Perry

From his Friend

Thomas Hammond

The Harvard Shaker community is not known to be an oval box-producing branch of the Society. Unlike New Lebanon, Canterbury, and Alfred, they did not cultivate an oval box industry, but that does not mean they did not make boxes for community use. Elder Thomas Hammond, Jr. (1791-1880), listed as a “carpenter” in federal census data, is best known for his joinery and overseeing the production of chairs for the Harvard community. In Shaker Furniture Makers (1989), the authors note a selection of journal entries documenting Brother Thomas’ chairmaking, highlighting a January 1839 notation that states, “Elder Brother Thomas Hammond… has made all the chairs for many years.” In 1841-42, he served as foreman, producing a total of 339 chairs: “There was put at the office (for sale) 83 common, 3 rocking chairs with arms, and six small ones—92 in all.”

Although Elder Thomas’ activities as a church leader and farmer are well documented in manuscripts in the collection of Fruitlands/The Trustees, (he compiled numerous daybooks), very little documents his activities in cabinetry. The only entry that opens up the possibility of Elder Thomas’ involvement in oval box production is through a record of his work in an adjacent craft: bentwood sieves. On December 15, 1849, Elder Thomas hauled maple logs to the mill for sieve rims and he worked at the mill planning sieve rims with his new machine. This planning machine could also have been used to produce the maple sides and rims of oval pantry boxes.

Journals in the collection of Western Reserve Historical Society (WRHS) written by Elder Joseph Hammond (1789-1849), Elder Thomas’s biological brother, also contain many references to the sieve industry at Harvard. Intermittently throughout 1826 and 1827, he documents his progress making and finishing sieves, alluding to the production of oval boxes as well. Notably, Elder Joseph documents:

1826 jul 11: Wrought at shaving down the laps of 6 Doz wide rims for Large sieves… finished oval molds.

1827 apr 30: Wrought made 2 small oval sieve rims & made 2 small Oval Box Sieves & got out & cut in the headings & finished & carried to the office about 10 Oclock P.M. 3 Large Oval Apothecaries Sieves for Hosea W[inchester]. These are the last of 10 Sieves I have now made.

1827 dec 12: Wrought at plaining, bending, & nailing 12 rims for Boxes to keep copper & Iron tacks in.

1827 dec 15: Wrought finished Boxes & numbered them.

Ministry journals written by Elder Grove Blanchard (1798-1880), also in the collection of WRHS, reinforce the history of oval box production at Harvard. On August 9, 1837, he records:

Wednesday, Showers, AM; PM quite rainy, AM Brethren hoe beans, turnips, and potatoes, at Yellow house place, and all get wet to their skins. – Grove and John with the above company, PM – Grove begin to work some on Oval Boxes…

And, again, on March 21 the following year:

Wednesday, Fair, Grove at Boxes, bent 4 Dozen and nailed some.

Most likely, this inscribed box was made by one of the Hammond Elders—its amateurish charm does not connect it to the more skillful hands of Elder Grove, who produced dozens of boxes at a time. It seems likely that a craftsman with experience producing furniture or sieves—a form not as refined as oval boxes—was the maker of this piece. The question is: was this box made in the second quarter of the nineteenth century when Elder Joseph was producing sieves (before he died in 1849)? Or, is the of a later date of manufacture and, therefore, made by Elder Thomas?

The inscription may provide a clue. Charles H. Perry was born in the early 1830s in the Buffalo area—possibly Canada. Records on Perry are scant, but we know that he was brought to the community by Sister Mercy Dring (1805-1881), who was the biological sister of Sister Elizabeth Persons (1802-1874). Brother Charles was a member of the East Family from 1870 before entering the Church in 1877. Just three years later, he left the community, shortly time before Elder Thomas died in December of 1880.

Was this oval box a gift welcoming Brother Charles to the Church Family in 1877, or was it a gesture of best wishes upon his departure in 1880? Either way, it seems likely that Elder Thomas himself made, finished, and inscribed this box for Brother Charles. Perhaps further research will reveal more about the relationship between the two Shakers and the experience of Brother Charles as a Harvard Believer. Until then, this Box represents the only material evidence of oval box making at Harvard and its unique construction may provide clues that help identify additional boxes attributed to this community.

Resources cited:

Jerry V. Grant and Douglas R. Allen, Shaker Furniture Makers (Hanover/London: University Press of New England, 1989), p. 66.

Images:

Shaker Oval Storage Box (Harvard, MA), c. 1875. maple, pine, and copper, original stain and varnish surface; 2 ½ h. x 5 ½ w. x 3 9/16 d. inches. Photos: John Keith Russell.

Historic images:

www.harvardshakers.com

Thank you to Roben Campbell and Jerry V. Grant, who contributed important research to this post.

The Watt & Jan White Shaker Collection

– Posted from Manchester, NH | August 2023 –

Watt C. White Jr. (1939-2022) had an enduring passion for collecting. His journey began at just ten years old when he wandered into a shop on Madison Avenue in New York City and purchased four Britain Toy Soldiers. From that moment, he was hooked. Watt dedicated much of his life to becoming a well-informed, generous collector with an acute eye. In addition to cultivating a significant collection of painted Shaker boxes, Watt was drawn to other examples of American folk art, acquiring important collections of weathervanes and whirligigs, mid-20th-century cast iron doorstops, 19th-century ink bottles and wells, United States postal history, and more.

“I met Watt and Jan about fifteen years ago when they came into my booth at the ADA/Historic Deerfield Antiques Show and bought a little red Shaker box. When he handed me a check, I realized they lived in the town next to South Salem but had never come into the shop. It was from this very first interaction that I began to understand Watt’s most distinguishing quality: his steadfast sense of discipline. He was a prolific collector with a range of interests—from whirligigs and weathervanes to doorsteps and postage stamps. Even so, he would only go to certain venues or dealers to acquire specific forms in a very controlled way. When Watt defined a sphere of object that captivated him, his modus operandi was to collect. When he reached a certain point, he’d be sated, and the collection would go to auction—he’d be done.

Watt decided that the Shaker Oval Box was an important object and, through this, we were able to begin a relationship. He began making monthly trips to my shop, (usually after I had alerted him of some new acquisition), where we would look at boxes and have lunch. The concept of stacking boxes was not something that interested Watt. He’d look at each box as a singular object and make a decision based on whether or not it filled the criteria by which he wanted to own it. Over time, he assembled over forty Shaker boxes—most of which are painted and stained in an array of colors.

A few years ago, Watt and Jan decided that, unlike their other collections of folk art which were sent to auction, they wanted me to handle the disbursement of his Shaker Oval Boxes. I am honored to be the recipient of this exceptional personal collection, but more significantly, the beneficiary of Watt and Jan’s trust, loyalty, and friendship.“

– John Keith Russell

Born in Winston-Salem, NC, Watt graduated from Wake Forest and began his career at RJ Reynolds. He attended the PMD program at Harvard Business School and remained in Boston to serve as the head of human resources for the Kendall Corporation. In 1981, Watt relocated to Stamford, CT, where he and his family resided for 41 years. Initially, he held a high-ranking position in human resources at Colgate-Palmolive in New York before going on to travel the world as a Management Consultant for Change Management Group. Ultimately, Watt established his own firm, Watt White Management Consultants.

In addition to his passion for collecting, Watt was an avid athlete. He was a record-setting championship sprinter in college as well as a lifelong distance runner, completing fourteen marathons. He was also a skilled golfer, carding two, lifetime holes-in-one and scoring a 70 on the famous Pinehurst No. 2 golf course. In later years, Watt loved walking laps in Scalzi Park and playing ball with his cherished Granddaughter.

“It’s always a bittersweet thing to let a collection go,” said Watt in advance of the 2021 auction, Color and Form: The Important American Folk Art Collection of Jan and Watt White. “We sincerely enjoyed the process and the people we met along the way, and we truly cherish these items… All things considered, it is genuinely exciting to know that others out there will now share some of the joy Jan and I shared in acquiring and living with these objects.”

After a lifetime of collecting, Watt passed away in October of 2022. He is survived by his loving wife, Jan, sons Watt White III and Ward White, daughter-in-law Robyn-Ziegler White, and granddaughter. His family retains his original collection of four Britian Toy Soldiers, which have always been displayed proudly on a shelf in the den.

In August 2023, John Keith Russell is pleased to present the Watt & Jan White Collection, an outstanding group of forty painted and stained Shaker oval storage boxes offered exclusively at Antiques in Manchester, The Collectors’ Fair. Previously, the Whites’ collections of Americana have been offered by Jeffrey S. Evans in 2021, Matthew Bennett in 2002, and Charles G. Moore Americana in 1996.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE WATT & JAN WHITE SHAKER COLLECTION

represented by John Keith Russell at Antiques in Manchester

“a fearless battle axer against the lives of evil doers”*

Elder Micajah Tucker’s Canterbury Dining Chairs

– Posted from Miami | November 2022 –

There’s no better way to build community than to share meals together. “A family is a group of people who eat the same thing for dinner,” remarked writer Nora Ephron. This is certainly true when looking at the communal lives of the Shakers, for whom mealtimes were nourishment for body and spirit.

There was a great deal of ritual surrounding Shaker families coming together to dine. Each mealtime was signaled by the toll of a bell, after which the Shakers would enter the dining room and sit with their respective genders—Brethren on one side, Sisters on the other. Beyond the clatter of filling plates with whole grains, vegetables, meat, and fresh baked bread and pie, meals transpired in silence to provide space for thanks for abundant food, good health, and a loving community.

The Shakers created monumental Trestle Tables of astounding lengths to accommodate meals for families of up to 100 Believers, who would pull up shared, backless benches to the tables to dine. According to Shaker Elder Henry Clay Blinn (1824-1905), the benches “were not convenient, especially if one was obligated to leave the table before the others were ready. All were under the necessity of sitting just so far from the table.”[1]

In 1834, Elder Micajah Tucker (1764-1848) of Canterbury, New Hampshire, decided to retire the communal dining benches and produce individual spindle-back dining chairs. In A Current Record of Events from 1792 to 1885, a community journal documenting happenings at the Canterbury Shaker community, it is noted on April, 26, 1834:

“Our Dining Room tables having been newly stained and a sett[sic] of new chairs made for the dining room by Elder Micajah Tucker & Bro. Joseph Sanborn we occupy them to-day for the first time”[2]

One of the early New Hampshire Believers, Elder Micajah was chosen as a Deacon at the founding of the Canterbury community in 1792. He traveled spreading the Shaker gospel as a missionary for over a decade, before settling in Canterbury full-time in 1806 and serving as an Elder for the next 28 years. Upon his retirement from the ministry, Elder Micajah, who was a joiner and carpenter by trade, turned his attention to creating dining chairs.

The design of Elder Micajah’s Dining Chairs is emblematic of Shaker ingenuity. “There is no dirt in Heaven,” proclaimed Mother Ann Lee (1736-1784). Shaker design is an aesthetic motivated by faith. Comprised of concave crest rails, spindles, shaped seats, and turned legs, the low backs of Brother Micajah’s dining chairs were designed to fit discreetly under a Shaker dining table to facilitate cleaning, setup, and storage.

A rare and sought-after Shaker design, it is presumed that only 80-90 of these chairs were ever made. The design was influenced by the Windsor plank-bottom chair, with Elder Micajah’s version distinguished by boldly beveled seats and strongly canted legs. This set of four Dining Chairs is crafted from birch and pine, retaining their original red stain and varnish surface. On the undersides of the seats are Shaker markings in red paint: the numbers “2,” “18,” and “12.” According to Tim Rieman and Jean Burks in The Encyclopedia of Shaker Furniture (2003), “it is not known if [the numbers] represent a particular member, seat location in the dining room or other rooms in which the chairs may have been used,” (p. 415).

Regardless, the design of Elder Micajah Tucker’s dining chairs is icon within the canon of classic Shaker forms.

Cited:

*Henry Clay Blinn, Church Record, 1784-1879, 1892, p. 79. Collection of Canterbury Shaker Village (ms. #764).

[1] Ibid, p. 247.

[2] A Current Record of Events from 1792 to 1885, p. 57. Collection of Hamilton College.

Images:

Church Family Dining Room, Canterbury, NH, c. 1875. Photo: H. A. Kimball. Collection of Hamilton College.

Elder Micajah Tucker (1764-1848), Shaker Dining Chair, Canterbury, NH, 1834. Pine and birch, original red stain and varnish surface. 24 ¾” h. (seat: 17 1/8” h.) x 13 5/8” w. x 14” d. Photo: John Keith Russell

“Classic” New Lebanon Rocking Chairs:

a close look at the evolution of an iconic Shaker form

– October 2022 –

Few realize that the rocking chair is a relatively new furniture form. These days, they’re everywhere—decorating nurseries, sitting rooms, porches, airports, hotel lobbies, and even highway rest stops. Their ubiquity suggests a timelessness but, in truth, the first rocking appeared only about 250 years ago when American colonists began adding rockers to existing chairs. Before long, the swaying motion of DIY rockers proved to be relaxing and a welcome relief to tired, aching backs, and by the mid-19th century, rocking chairs were common fixtures in American homes.

The Shakers were among the first in the US to manufacture rocking chairs for use within the community as well as for sale to the world. Since utility is at the foundation of Shaker design, we imagine that it was the therapeutic effects of rocking that led to production, (as opposed to the leisurely porch vibes that rocking chairs were associated with at that time). Too, at the turn of the 19th century, the founding generation of Shakers was aging. According to the 1845 Shaker Millennial Laws, “One rocking chair in a room is sufficient, except where the aged reside,” (section X, no. 3). Rocking chairs were seats for those further along in years—thrones for the elder and senior to pursue the spiritual work of Shakerism in comfort.

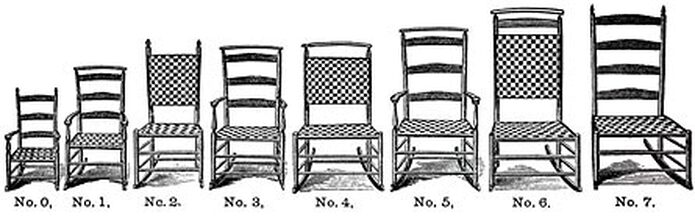

The earliest rocking chairs made by the New Lebanon Shakers are dated to the opening decade of the 19th century—the time when Shaker communities were in the process of being designed, built, and furnished. Within the spectrum of Shaker material culture more broadly—from architecture to furniture and handheld tool—there was a spirit of experimentation as designs were prototyped, formalized, and disseminated amongst all of Shaker society. This iterative process can be observed in the rocking chair which, over a century, evolved from a bespoke object made for an individual Elder or Eldress to a standardized template manufactured in eight sizes.

Throughout the 19th century, the Shakers of New Lebanon finetuned the rocking chair form and streamlined production. The chairs became lighter, more refined, and balanced in their proportions. Over time, technology changed as well—new tools and techniques such as water-powered lathes, steam-bending, and the advent of the circular saw allowed the Shakers to create more ergonomic chairs with greater efficiency and a reduction in handwork.

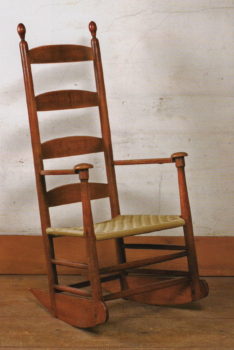

Of course, the tailored nature of Shaker furniture made for community use combined with the unique experimentations of individual turners, (or chairmakers), have resulted in myriad variations—there is no truly “iconic” New Lebanon Shaker rocking chair. Piecing together a cohesive trajectory of rocking chair design proves challenging; however, the material record existent today provides some compelling case studies for examining pre-production rocking chairs—their underlying principles, fabrication process, and presumed purpose.

In general, the rocking chairs made at New Lebanon can be divided into five phases:

· Early, 1790s-1820s. Early Shaker rocking chairs exhibit a charming crudeness—they tend to be physically heavy and ofttimes visually awkward.

· Classical, 1820s-1850s, the period of greatest creativity. Classical chairs express the Shaker ideology of simplicity, utility, and beauty—they become lighter, more visually balanced, and exceptionally crafted by hand. It is presumed that the majority of these chairs were created for community use. With variations in arm placement, seat height, and the position of slats, this bespoke method of production indicates that individual chairs were made to the specifications of individual Shakers.

· Transitional (Early-Production), 1850s-1874. Until 1863, the chair industry was managed by the New Lebanon Second Family, which operated the chair factory six months per year, employed three people, and had an annual production of approximately 600 chairs.[i] After 1863, production was overseen by Elder Robert M. Wagan (1833-1883) of the South Family. During this Transitional period, chairs were mostly crafted by hand, which retained subtle variations and imperfections, and a system of labeling chairs by size was introduced.

· Wagan Era (Peak-Production), 1874-1923. Elder Robert M. Wagan oversaw the transition to the standardization of Shaker chairs, offered in eight sizes and a selection of styles, as well as the complete mechanization of the fabrication process, which relied on standardized components. In 1874, Wagan introduced a trademark decal, authenticating the South Family chairs as Shaker.

· Perkins-Barlow Era (Late-Production), 1923-1940. In 1915, Brother William Perkins (1861-1934) took over the management of the South Family chair factory. With Sister Lillian Barlow (1876-1942), they oversaw operations through a devastating fire in 1923. When the chair factory was reopened, changes in staff and equipment resulted in modifications in the design and fabrication of the last Shaker chairs.

The intent of this blog entry is to delve into the Classical period of Shaker rocking chairs, examining three examples of rockers produced between the 1820s and 1850s. (Please note: none of these chairs are in available inventory! Contact us directly to discuss what we currently have to offer.)

The first, affectionately nicknamed “Boots,” came to us via the Robert & Hazel Belfit Shaker Collection, which was presented at the Antiques in Manchester fair in August 2022.

The second, “Five Slat,” is a monumental Elder’s chair in its original red stain that came back through the shop recently because it needed a new taped seat.

The third, “Cindy’s Chair,” (named for its owner, Cindy Russell, who received it from John as a wedding present), is an elegant Eldress’ chair with the rare feature of a cushion rail, (also called a shawl bar), in lieu of finials.

These three chairs are exceptional examples of Classic New Lebanon rocking chairs made between the 1820s and 1850s—the center of the overall iterative arc of the form, when Shaker design and craft reached its peak. What’s interesting is that certain elements of the chairs might date them earlier, while other details indicate a later date of manufacture. It’s this remixing of features that leads us to date these examples within the Classical period—we cannot definitively say which pre-dates the other, (although we can argue about it at length!).

Let’s begin by examining the chairs’ similarities. The three chairs have:

- rocker blades of a thicker weight (when compared to later production chairs) and distinctive shape—pointed front, concave between posts, and a shaped blade end.

- posts fitted around the rocker blades that are squared off on the bottom edge and secured with wooden pins (Five Slat and Cindy’s Chair) or ferrous screws (Boots).

- front posts with a concave taper from seat to arm ending with a turned collar that is mortised into the underside of the circular handholds.

- side scroll arms that are rounded on the inside, beveled on the outside, and tenoned into the rear posts.

- non-graduated, beveled back slats.

- slightly tapered, straight back posts (approx. ½” graduation from bottom to top)

Overall, there is an undeniable refinement that has happened between Early rockers, which look like armchairs fitted with flat pontoons, and these lighter, more graceful chairs. The delicate arc of the scroll arm tenoned into the back post is a particularly distinctive feature, which gets further and further refined into the early 1870s (before the transition to the Wagan Era cut arm). Interestingly, it is what distinguishes these chairs from each other that makes them truly Classic Shaker rocking chairs. Created as community furniture, these examples are virtually one-of-a-kind—bespoke creations that were Shaker-made and presumably Shaker-used.

For example, Boot’s boots are the enlarged turnings at the base of the posts that provide added strength to the joint between the rockers and the post. Perhaps a more robust chair made for a weighty Shaker, this feature is most often dated to 1830s and 40s. Our best guess is that the boots proved to be a case of over-engineering, added girth that proved structurally unnecessary and was eventually eliminated from the design. It’s worth noting that Boots was made for and remained within the New/Mount Lebanon community until it was acquired by Robert and Hazel Belfit in the early 20th century. This was a well-used chair—a solid chair of sturdy design and construction that withstood generations of use.

Five Slat is a rare, statuesque design most likely created for a very tall Shaker. Well-proportioned and refined, Five Slat is visually the most successful of these three, representing the aesthetic apex of a New Lebanon Classical chair. Seen only on a small group of chairs known, the illusive fifth slat is a highly sought-after variation. Could this chair be an exercise in vanity, demonstrating either the turner’s skill or the spiritual stature of the user? Why aren’t there more five slats existent today? We speculate it may have something to do with the technical requirements to make such lengthy back posts. Lathes were not infinite in their capabilities—the additional six inches to accommodate a fifth back slat could only be achieved by a skillful maker working on a lengthy lathe.[ii]

Cindy’s Chair, with its rare cushion rail, is one of only three examples with this feature known. During the Wagan Era, the cushion rail was embraced as an available variation in the Mount Lebanon chair catalog, which promoted substituting a bar across the back posts so a cushion could be hung vertically down the back slats. The Shakers would make these cushions as well, advertising, “the heavy wool plush with which we cushion our chairs is a material particularly our own. It is made of the best stock and woven in hand looms… We have all the most desirable and pretty colors represented in our cushions, and they can be all one color, or have a different color border, or with different colored stripes running across the cushion.”

What was an established product in 1874, decades prior, was a mere prototype. Of the three rockers discussed here, Cindy’s Chair is perhaps the best example of a Mount Lebanon pre-production chair, most likely made towards the end of the Classical period. We opine that the cushion rail proved to be such a utilitarian and desirable feature that it was carried through Transitional period and into production.

We will delve into the history of Transitional Rocking Chairs in a future blog post. Sign up for our e-newsletter to receive updates on the blog, events, and featured inventory.

[i] Charles R. Muller and Timothy D. Rieman, The Shaker Chair (1984), p. 169.

[ii] It’s worth noting that 20th-century Perkins/Barlow chairs, which could run quite large, had finials applied to the back posts with glue. Was this also because of a limited lathe capacity? Or, was it because some components were contracted by the Shakers and fabricated offsite, and others were still Shaker-made?

Images:

Mother Ann’s Chair [a converted, non-Shaker, Windsor-style chair], c. 1770s. Collection of Fruitlands Museum (Harvard, MA)

Miriam Wall and Aida Elam, Canterbury, NH, 20th c. Collection of Hamilton College

Illustrated Catalogue and Price List of the Shakers’ Chairs, c. 1900

Early Shaker Rocking Chair, New Lebanon, NY, c. 1810. Collection of Hancock Shaker Village (Pittsfield, MA)

Classic Shaker Rocking Chair, New Lebanon, NY, c. 1830. Courtesy of John Keith Russell

Transitional Shaker Rocking Chair, Mount Lebanon, NY, c. 1860. Courtesy of John Keith Russell

Wagan Era Shaker Rocking Chair, Mount Lebanon, NY, c. 1885. Courtesy of John Keith Russell

Perkins/Barlow Shaker Rocking Chair, Mount Lebanon, NY, c. 1929. Collection of the Art Complex Museum (Duxbury, MA)

“Boots” (left); “Five Slat” (center); “Cindy’s Chair” (right). Courtesy of John Keith Russell

The Robert & Hazel Belfit Shaker Collection

– August 2022 –

In the 1920s, Robert and Hazel Belfit began acquiring Shaker furniture, tools, domestic objects, and ephemera that, by the 1960s, would become one of the most significant collections of Shaker material obtained directly from the Shakers.

“As time goes on, primary material—material acquired directly from the Shakers and retained by a single family—has become increasingly rare. Rob and Hazel Belfit had a passion for the Shakers and their culture that, today, has transcended four generations. It is an honor that Ashley Freinberg, Rob and Hazel’s descendant, has entrusted us with finding new stewards for these artifacts. We share her hope that these pieces are understood and appreciated by their next owners as they have been by the family.” – John Keith Russell

Each object in the Belfit Shaker Collection embodies a connection to the Shakers themselves. Following their first visit to the Mount Lebanon Second Family chair factory in 1924, Robert and Hazel maintained meaningful relationships with the Shakers at Mount Lebanon as well as other active communities including Watervliet, New York, Hancock, Massachusetts, Canterbury, New Hampshire, and Sabbathday Lake, Maine. As their friendships grew, so did their collection. The Belfits’ frequent correspondence and visits with the Shakers established them as keen, responsible, and understanding stewards of the Shaker legacy, and the Brethren and Sisters conveyed their appreciation when placing objects in their care.

Robert and Hazel Belfit were drawn to Shaker material that enhanced their lifestyle. Their home in Watertown, Connecticut, highlighted Shaker-made pieces throughout. The Belfit family was raised amidst treasured objects—they dined on a Shaker table, stored their toys in a Shaker cupboard, and were lulled to sleep in a Shaker rocking chair. The passion for Shaker material and history was omnipresent, and this appreciation persists to this day.

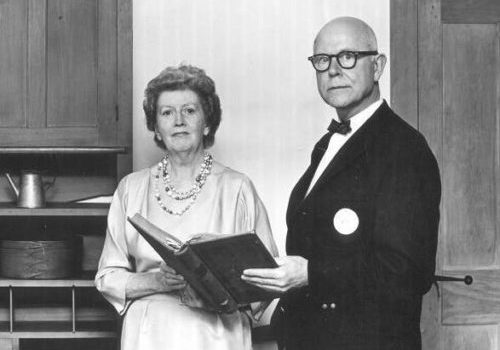

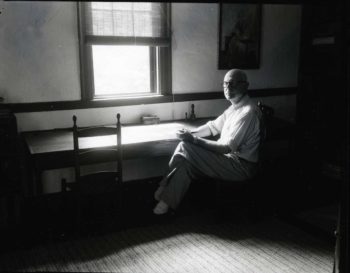

Photos: Hazel Belfit, Robert William Belfit, and Eldress Rosetta Stephens at Mount Lebanon, NY, c. 1940s (top); Robert William and Hazel Belfit, c. 1972. Collection of Ashley J. Freinberg.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE ROBERT & HAZEL BELFIT SHAKER COLLECTION

represented by John Keith Russell at Antiques in Manchester

MORE ON ROBERT & HAZEL BELFIT:

Designs for Working Women: Thoughts on the Shaker Sewing Desk

– Women’s History Month | March 2022 –

“The imaginative faculty, seeking to clothe utility in ever-new forms, often evolved original units such as the sewing desks, so called, designs of which vary greatly in different societies, even within a given community.”

– Edward Deming Andrews, Shaker Furniture (1939)

Today, the Shaker sewing desk is a classic and sought-after form. Usually comprised of a worktable over drawers with a gallery of smaller drawers above, this uniquely Shaker design represents a 50-year evolution that demonstrates the Shaker principles of creative reuse and adaptation. Built to accommodate various Sisters’ tasks, there are myriad variations on the Shaker Sewing Desk: the incorporation of pull-out, expandable work surface; additional drawers on the left or right of the lower case; pegs affixed to the apron; fold-out leaves; a gallery floating above the desk; innumerable configurations of upper drawers and cabinets; and the addition of a shallow, under-hung drawer to hold patterns.

The origin of the sewing desk is rooted in the simple worktable, developed in the early-19th century. Soon after, drawers were added to accommodate sewing accessories and tools and, by the mid-century, removable add-on galleries of multiple drawers were often constructed to rest on top of the work surface. What we now think of as the classic Shaker Sewing Desk was designed and built with an incorporated gallery of drawers, prototyped after the design of the table plus the add-on.

The iconic Shaker sewing desk form originated in Northern New England—the Canterbury and Alfred bishoprics; however, New/Mount Lebanon developed a distinctive sewing desk as well. In the History of the Shakers at New Lebanon, Brother Isaac Newton Youngs wrote: “We find out by trial what is best, and when we have found a good thing… we stick to it.” [i] Shaker design was intentional—it was purpose and person-driven, embodying the idea of every force evolves a form. If a Shaker Sister required a specific surface, storage, and orientation for a particular task, it was created for her. Objects were conceived and crafted with the utmost intention.

Many of the most outstanding examples of imbuing intention into design are illustrated by objects related to the work of women. Though Shaker communities relegated tasks along traditionally gendered lines—Brethren worked the fields, farms, mills, and workshops, Sisters handled the domestic tasks of cooking, cleaning, sewing, laundry, etc.—the two spheres supported each other and were upheld equally as contributing to the functioning and overall productivity of a Shaker community.[ii]

Historic photographs illustrate the ways that sewing desks were used by Shaker Sisters in their workshops and retiring rooms. Sisters were always kept very busy producing items for the community as well as for sale to the World. According to Andrews, “the hands of many sisters, young and old, were required to supply stockings and underclothes, shirts and collars; to mend clothes; to finish the cloth-and-leather gloves; to make seed bags; to line and furnish sewing boxes; to weave the fine ash and poplar baskets; to braid palm leaf for mats and bonnets; and to make the fans, dusters, pen wipes, cushions, spool stands and numerous other articles of handcraft so useful to a well-ordered communal life and so prized by the people of the world.” [iii]

As early as 1813, Brother Isaac Newton Youngs recorded that the Sisters began “little by little to make baskets for sale,” and they quickly expanded production to include many other kinds of goods—from hats and brushes to herbs and preserved items. [iv] The first Shaker store was opened by the New Lebanon Church Family in 1827 and, by the 1830s, production of goods for sale reached significant proportions. Fancy goods or fancy work—domestic objects made by the Sisters for a predominantly female market—became an economic mainstay for the Shakers. By the 1870s, the overall ratio of women to men was roughly two to one (higher in certain communities). Brother John Vance of Alfred wrote in his journal that such male tasks as manufacturing woodenware and producing tanned goods, seed, and herbs were largely either “dropped years ago” or “destroyed” by competitors. The “only branch of manufacture in the Society,” according to Vance, was the Sisters’ fancy work. [v]

This rare Shaker Sewing Desk, which descended in a New Lebanon, NY-based family, was created in the third quarter of the 19th century when the Sisters’ economy was vital to the fiscal viability of the Shakers. Illustrated in the Encyclopedia of Shaker Furniture (2003), this piece was originally designed and constructed as a sewing desk and has never been altered. The form is relatively typical of a Mount Lebanon desk; however, it has an unusual square-to-round transition on the leg and a horizontal bone escutcheon. The bone buttons on the legs just below the perimeter of the base are thought to have held a fabric bag that hung under the desk—a feature that was popular in the Federal period.

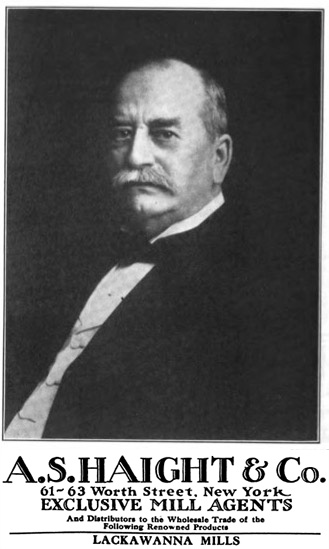

The provenance of this piece is tied to Abner Sherman Haight (1839-1920), founder of the A. S. Haight company, which specialized in wholesale distribution of knit cotton and wool long underwear. Haight was born in New Lebanon, NY, and he maintained a farm of 1,500 acres near the New Lebanon Shakers. [vi] There is documentation that Haight commissioned a Shaker Cupboard over Drawers, which was made and delivered to his home in 1853. Haight family oral history has relayed that additional pieces of furniture were commissioned to furnish his New Lebanon residence as well as his hunting cabins. Since this Desk was acquired from the Shakers at Mount Lebanon, was it one of those special commissions or was it used by the Shakers?

Upon Mr. Haight’s death, the Sewing Desk was inherited by his son, Charles Sherman Haight (1870-1938), who moved it to his home, “Unity Lodge,” in 1892. From there, it was moved to a hunting lodge also owned by Charles, before being inherited by Abner’s granddaughter, Harriet Schutt (1908-1981), who moved it to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and then to Pasadena, California. Subsequently, the piece descended to Harriet’s son, Kenneth Haight Schutt (1934-2018), and grandson, Geoffrey Mann Schutt (b. 1963).

Overall, this Sewing Desk is in fine, original condition. It retains its original stain and varnish surface with a subsequent clear over-finish that was applied at a later date.

References:

[i] Isaac Newton Youngs, History of the Shakers at New Lebanon, edited by Glendyne R. Wergland and Christian Goodwillie, (Clinton, NY: Richard W. Couper Press), 2017

[ii] Glendyne R. Wergland, Sisters in the Faith: Shaker Women and Equality of the Sexes, (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011)

[iii] Edward Deming Andrews, Shaker Furniture,(New Haven: Yale University Press, 1939), p.86

[iv] Youngs (edited by Wergland and Goodwillie), p.102-103

[v] Beverly Gordon, “Victorian Fancy Goods: Another Reappraisal of Shaker Material Culture,” Winterthur Portfolio, v. 25, no. 2/3, (Summer/Autumn 1990), p.111-129

[vi] A. S. Haight obituary, Underwear & Hosiery Review, (March 1920), p.126

Images:

Sewing Desk, Mount Lebanon, NY, n.d. Photo: Dexter Photo Co., Hartford. Collection of Winterthur (SA 611)

Sewing Desk, New Hampshire Bishopric, ilustrated by Ejner Handberg, Measured Drawings of Shaker Furniture and Woodenware (1980), p. 12-13

Sisters’ Work Room, Mount Lebanon, NY, n.d. Collection of Shaker Museum Mount Lebanon (1960.12246.1)

Adeline Patterson, Hancock, MA, 1957. Photo: William Tague, Berkshire Eagle.

Shaker Sewing Desk, Mount Lebanon, NY, c. 1870. Photo: John Keith Russell

Abner Sherman Haight, n.d. Published in Underwear & Hosiery Review, (March 1920), p.126

One-Drawer Sewing Stand given to Edward Deming and Faith Andrews by the Hancock Shakers, Christmas 1930

– February 2022 –

“Pandora’s box was empty compared with our first glimpse beyond the kitchen door,” reflected Faith Andrews on the first visit that she and her husband, Edward Deming Andrews, paid to the Hancock Shaker community in 1923.[i] Who would have guessed that a stop for a loaf of freshly baked bread would spark a life’s work? In their memoir, Fruits of the Shaker Tree of Life, the Andrewses recalled this fortuitous moment that led to decades of research, collecting, and curating that, ultimately, elevated the achievements of the Shakers from obscure footnote to formative touchstone within the history of American culture and design:

“A soft voiced Shaker sister welcomed us warmly. We bought two loaves of bread. And in the long clean ‘cook-room’ we saw much besides; a trestle table, benches, rocking chairs, built-in cupboards, cooking arches, all beautiful in their simplicity. Later, eating the bread, we knew that our appetite would not be satisfied by bread alone.”

– Faith Andrews interviewed by Robert F. Brown, January 14, 1982

This rare, Sewing Stand was a Christmas gift to the Andrewses from the Eldress Fannie Estabrook (1870-1960) on behalf of the Hancock Shaker community. Unique to the Hancock Shakers, there are only three examples of this form known. The Andrews’ stand is a singular variation, comprised of mortised spiderlegs, a basswood top, a single under-hung drawer that can be pulled from either side, and a finely dovetailed yoke threaded into a turned cherrywood pedestal. The underside of the drawer bears an inscription:

Presented to our dear friends –

Faith and Edward Andrews

Christmas 1930

From your Shaker friends

Hancock – Mass.

Fannie Estabrook

Beginning in the 1920s, the Andrewses purchased, sold, traded, and donated thousands of objects that, today, are highlights of important public and private Shaker collections. Their ability to assemble such a diverse array of material—as well as document, publish, and exhibit its history and meaning—was largely indebted to the collaboration of the Shakers living at the time. As summer residents of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the Andrewses were particularly close with the Shakers at Hancock, (later, they would become full-time residents of Richmond, MA—a town neighboring the village). Sister Alice Smith (1884-1935) was their first elderly Shaker friend. Most likely, it was Sister Alice who first opened the door 1923 and was their gateway to the rest of the community.

During their visits to Hancock, the Andrewses were shown rooms full of furniture no longer in use due to the community’s dwindling numbers. “Almost everything had its price,” recalled Faith in a 1982 interview.[ii] It is unclear how the availability and value of items was determined, but it is certain that Eldress Fannie Estabrook was greatly involved.

Appointed Eldress in 1929, Estabrook and Eldress Caroline Helfrich (1836-1929) oversaw Hancock’s Church Family. The Eldresses would have been obligated to report all financial decisions to Trustee M. Frances Hall (1876-1957), (who lived in the Trustees’ Office rather than the Church Family dwelling), but it is unclear if proper protocol was observed when it came to the selling of their communal possessions. As well, there is documentation and personal testimony confirming that Sister Alice was ferreting items to her friends “under the table.”[iii] She not only offered things to the Andrewses—notably a collection of gift drawings, but Alice also helped Charles C. Adams assemble a significant Shaker collection for the New York State Museum.

A group of more recent Shaker scholars have written critically about the Andrewses and their legacy. As scholars and dealers of American antiques, they are suspected of sacrificing historical integrity in service of monetizing their own collection—a collection that some see as the result of exploiting a society in decline and the elderly women at the helm. Nonetheless, the gift of this Sewing Stand is evidence of the intimate relationship between the Andrewses and the Hancock Shakers—Eldress Fannie in particular. Indeed, we owe the existence of this Stand and many of the most outstanding objects designed and made by Shaker hands to the Andrewses and their intrepid desire to imbue Shaker with the significance it deserves. The Andrewses are a part of Shaker history, and this Sewing Stand is a reminder of the profound importance of their work.